Introduction

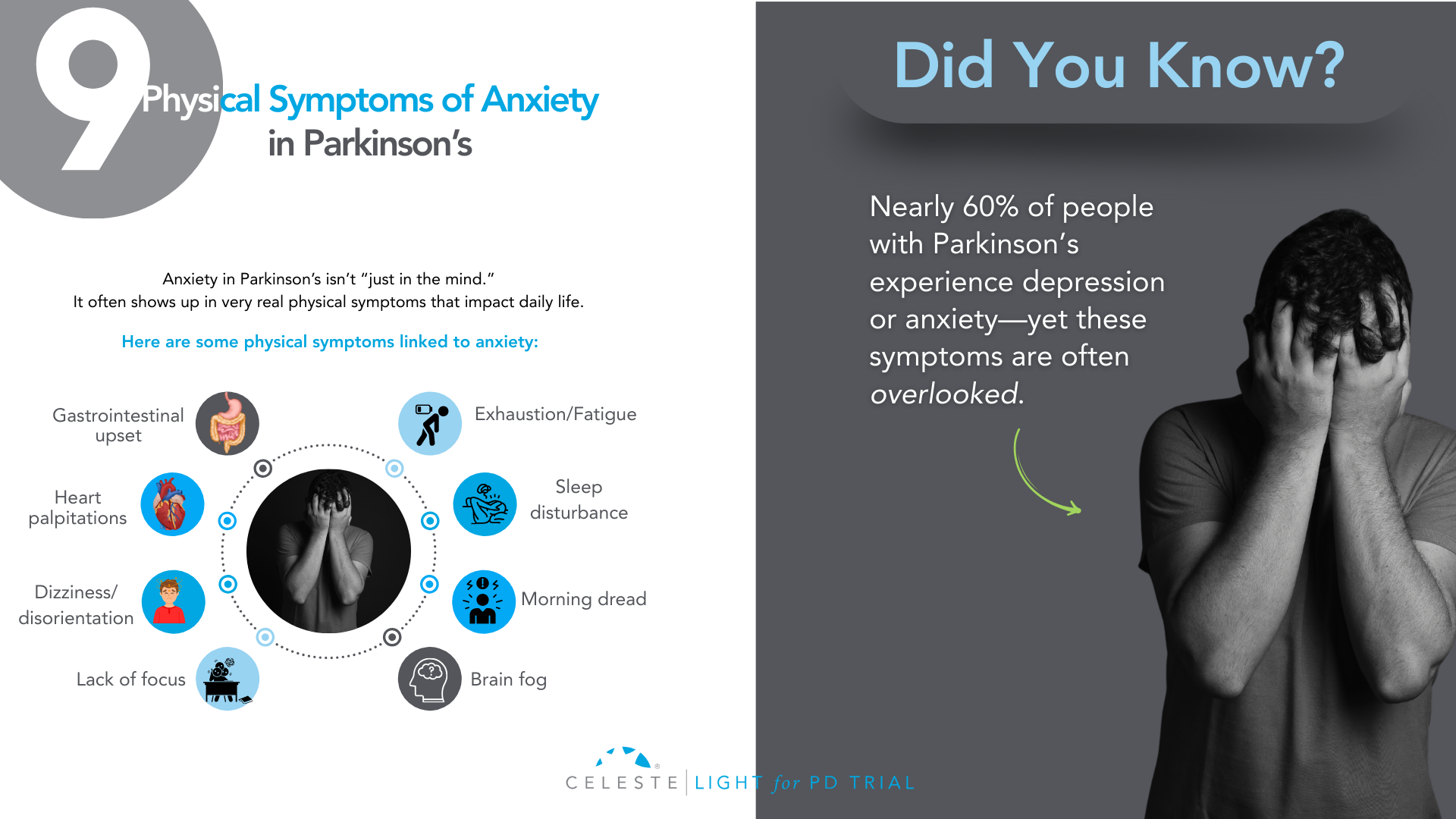

Did you know that at least 50% of people with Parkinson’s Disease (PD) will experience some form of depression during their illness, and up to 40% will face a significant anxiety disorder?

If you’ve been grappling with your mood, you are far from alone. For too long, the conversation around Parkinson’s has focused almost exclusively on the visible, motor symptoms like tremor, stiffness, and slowness.

But as you know, that’s only part of the story. The invisible challenges—the ones that happen inside—are often the heaviest to carry.

Many people, including doctors in the past, assumed that feeling down or anxious was just a natural emotional reaction to being diagnosed with a chronic illness.

While that can certainly be a factor, we now understand something much more profound: depression and anxiety are a core, biological part of the disease itself.

The same changes happening in your brain that affect movement are also affecting the chemistry of your mood.

This isn’t just a side issue; for many, it’s the main issue. It’s the hidden struggle that can impact your quality of life even more than the physical symptoms.

But here is the most important message: it is treatable. You do not have to “just live with it.”

This guide will walk you through this. We will explore why these feelings happen and look at what they look like in PD. This guide will discuss their impact on you and your loved ones. Most importantly, we will cover effective treatments. We will show strategies that can help you. You can reclaim your well-being.

The Celeste (Light for PD) trial shows promising results with a non-invasive approach to managing depression in Parkinson’s. Early findings point toward better support and improved quality of life. Find out how you can get involved.

Why Mood Changes Are Part of Parkinson’s?

To understand why mood changes are so common in Parkinson’s, we need to look beyond dopamine.

While PD is mainly caused by a loss of dopamine-producing cells, this is just one piece of a much bigger puzzle. The neurodegenerative process affects other crucial brain chemical systems as well. Think of it as a “neurotransmitter triad” involving dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine.

Role of Neurotransmitters

- Dopamine: This chemical is famous for its role in movement, but it’s also fundamental to our brain’s reward and motivation system. When the dopamine pathways that govern pleasure and drive are damaged, it can lead directly to apathy (a lack of motivation) and anhedonia (the inability to feel pleasure), which are core symptoms of depression.

- Serotonin: This is perhaps the most well-known mood-regulating chemical. The brain changes in PD also cause a significant loss of serotonin-producing neurons. This isn’t a side effect. It’s a direct hit on the system that helps keep our mood stable, our anxiety in check, and our sleep regulated. This direct link is a major reason why depression is so prevalent in PD.

- Norepinephrine: This chemical is essential for energy, focus, and our response to stress. The part of the brain that produces norepinephrine is also significantly affected in Parkinson’s. A drop in this chemical can contribute to the profound fatigue that so many experience, as well as to both depression and anxiety.

This complex, multi-system chemical imbalance explains so much. It tells us that what you’re feeling is real and has a physical cause. It also highlights one of the most compelling pieces of evidence: depression and anxiety often show up before any motor symptoms appear, sometimes by several years.

This strongly suggests that the mood-regulating parts of the brain are among the first to be affected by the disease process. Recognizing this can be empowering. It reframes your emotional struggles from a personal failing into a manageable symptom of your condition, just like a tremor or stiffness.

What Does Depression and Anxiety Look Like in Parkinson’s?

One of the biggest hurdles to getting help is that depression and anxiety don’t always look the way you’d expect, especially with Parkinson’s in the picture. There’s a significant and confusing overlap between the symptoms of PD and the symptoms of a mood disorder.

This clinical mimicry is a major reason why mood disorders are so often missed. You might feel fatigued and assume it’s “just the Parkinson’s.” Your family might see your reduced facial expression (hypomimia or “masked face”) and think you’re withdrawn or disinterested, when in reality it’s the PD affecting your facial muscles.

This is why it’s so critical to talk specifically about how you’re feeling on the inside, not just what’s showing on the outside.

Let’s break down how these conditions can manifest:

Depression in Parkinson’s can include:

- Major Depressive Disorder: This is what most people think of as clinical depression, involving a persistent low mood, loss of interest or pleasure, and other symptoms that make it hard to function.

- Minor Depression or Dysthymia: This is actually more common in PD. You may not meet the full criteria for major depression, but you experience a chronic, low-grade sadness and other depressive symptoms that still significantly impact your quality of life.

- Intense Feelings of Despair: We need to address this with care and honesty. For some, depression can lead to intense feelings of despair and even thoughts of not wanting to be alive anymore. If you ever find yourself having these thoughts, it is a medical emergency and a sign that the depression has become severe. Please understand that these thoughts are a symptom of the illness, and they can be treated. It is crucial that you reach out for help immediately—contact your doctor, a support hotline, or a trusted person in your life without delay.

The Celeste (Light for PD) trial shows promising results in addressing depression in Parkinson’s. This innovative research is exploring an innovative and non-invasive approach to improve your parkinson’s symptoms. Learn more and see if participation is right for you.

Anxiety in Parkinson’s often takes these forms:

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD): This is a state of constant, excessive worry and nervousness that you can’t control. It can be accompanied by physical symptoms like a racing heart, sweating, or even a worsening of your tremor.

- Panic Attacks: These are sudden, intense episodes of overwhelming fear. In PD, they are often linked to medication “off” periods, when your motor symptoms return as your medication wears off. This can be terrifying, making you feel like you’re having a heart attack or can’t breathe.

- Social Phobia: This is an intense fear of being embarrassed or judged in social situations. It’s often driven by self-consciousness about visible symptoms like tremor, walking difficulties, or dyskinesias. This can lead to avoiding friends and family, causing profound isolation.

How Mood Impacts Your Life and Your Family?

If you’ve ever felt that your mood is a bigger problem than your tremor, you are not alone. Study after study has confirmed that for people with Parkinson’s, depression and anxiety are the single biggest factors that determine a person’s overall quality of life.

It’s not just about feeling sad; these mood states create a vicious cycle of disability that can touch every aspect of your life.

- Worsening Symptoms: Anxiety is known to make tremors worse. Both depression and anxiety are linked to more severe freezing of gait and the difficult “on-off” fluctuations.

- Undermining Self-Care: Depression saps the motivation you need to stick with your medication schedule, do your physical therapy exercises, and stay socially active—all things that are absolutely critical for managing Parkinson’s effectively.

- Accelerating Cognitive Decline: Mood and thinking are deeply connected. Untreated depression can make cognitive issues like problems with focus and attention worse, and over time, may even speed up the rate of cognitive decline.

This ripple effect extends far beyond the individual, placing an enormous strain on the family unit. For caregivers, managing a loved one’s psychiatric symptoms is often more distressing and exhausting than dealing with physical disabilities.

The caregiver’s well-being is directly tied to the patient’s mental state. It’s an incredibly stressful role, and studies show that a huge percentage of caregivers experience burnout and even clinical depression themselves.

Supporting the mental health of the person with Parkinson’s is one of the most important things we can do to support the health of the entire family.

Taking the First Step: Getting the Right Diagnosis

Given the challenge of symptom overlap, you have to be your own best advocate. Don’t wait for your doctor to ask about your mood. In the limited time of a neurology appointment focused on motor symptoms, it can easily be overlooked. You need to start the conversation.

Saying something as simple as, “I’d like to talk about how I’ve been feeling emotionally,” can open the door.

To help identify the problem, your doctor can use simple screening tools. These are short questionnaires that can quickly flag whether you need a more in-depth evaluation.

One of the most recommended for PD is the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15). It’s useful because it focuses more on the psychological feelings of depression and asks fewer questions about physical symptoms that overlap with PD.

The goal of screening isn’t to give a final diagnosis, but to identify that there’s an issue that needs attention. The gold standard is always a full evaluation with a trained mental health professional, like a psychiatrist or neuropsychologist, who can fully understand the nuances of your situation and recommend the best course of action.

Building Your Treatment For Depression and Anxiety in Parkinson’s

Pharmacology is a key part of the treatment plan for many people. It’s about rebalancing the brain chemistry that the disease has disrupted. While no antidepressant is officially FDA-approved specifically for Parkinson’s, several types have been shown to be safe and effective.

Note: This information is for educational purposes only. We do not recommend self-treatment or medication. Please consult a healthcare professional for your Parkinson’s symptoms and receive personalized care options.

Available Options

- SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors): These are drugs like sertraline (Zoloft) or citalopram (Celexa). They are often the first choice because they are generally well-tolerated. They work by increasing the amount of available serotonin in the brain.

- SNRIs (Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors): These are drugs like venlafaxine (Effexor) or duloxetine (Cymbalta). Because we know that both serotonin and norepinephrine are depleted in PD, these dual-action agents can be a very logical and effective choice.

- TCAs (Tricyclic Antidepressants): An older class of drugs, like nortriptyline, has some of the strongest evidence for effectiveness in PD. However, they come with more side effects (like confusion, dry mouth, and constipation) that can be especially problematic for older adults, so they are usually reserved for cases where other medications haven’t worked.

- Dopaminergic Medications: Sometimes, optimizing your Parkinson’s medication can itself have a positive effect on mood. Certain dopamine agonists (like pramipexole) have been shown to have antidepressant effects. And for anxiety or panic linked to “off” periods, adjusting the timing and dosage of your levodopa is often the most important intervention.

The key is working closely with your doctor. Finding the right medication and the right dose can be a process of trial and error, as suggested or followed by a healthcare specialist.

A thoughtful doctor will practice “symptom-focused prescribing,” choosing a medication that not only helps your mood but whose side-effect profile might help another symptom. For example, if you have depression and insomnia, a more sedating antidepressant might be a great choice.

Non-Medication Strategies For Depression and Anxiety in Parkinson’s

Medication is only one part of the solution. A truly comprehensive plan must include non-pharmacological approaches that empower you with skills and strategies to manage your mental health.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): CBT is considered a first-line treatment for depression and anxiety in PD. It’s not just “talk therapy.” It is a practical, skills-based approach that teaches you how to identify, challenge, and change the negative thought patterns and behaviors that keep you stuck. For example, it helps you challenge thoughts like “I’m a burden to my family” and work on behavioral activation—scheduling small, achievable, and enjoyable activities to counteract withdrawal and apathy.

- Physical Exercise: Exercise might be a miracle drug for Parkinson’s. A huge body of evidence shows this. Regular activity is a powerful treatment. It’s effective for depression and anxiety. It boosts brain chemicals. It improves sleep. It gives you a sense of control. Find something you enjoy and do it consistently. This can be walking, Tai Chi, or yoga. It can also be a boxing class for PD.

- Social Connection: Isolation is fuel for depression. A lack of social support is one of the biggest risk factors for developing a mood disorder in PD. This is why support groups—either in person or online—can be a lifeline. Connecting with other people who truly “get it” reduces feelings of isolation and provides a space to share experiences and coping strategies.

You’re Not Alone—The Power of an Integrated Care Team in Parkinson’s Depression and Anxiety

Navigating Parkinson’s can feel like trying to coordinate a dozen different specialists who don’t talk to each other. The future of high-quality PD care is moving away from this fragmented system toward an integrated, multidisciplinary team model.

This means having a team of professionals who work together, with you and your family at the center. Your team might include:

- Your Movement Disorder Specialist, who manages the overall disease.

- A Psychiatrist or Psychologist, for medication management and therapy.

- A Clinical Social Worker, to help you connect with community resources.

- Physical, Occupational, and Speech Therapists, whose work to improve your function and independence has a huge positive impact on mood.

In this model, everyone is on the same page, working toward the same goal: improving your overall well-being.

Conclusion

Your emotional well-being is not a “soft” issue. It is not a secondary concern. It is central to your care. The depression and anxiety you feel are real. They are biological. They are treatable.

The first step is to acknowledge the struggle. Start a conversation with your doctor. Talk to your loved ones. Adopt a proactive and multimodal approach. Combine medications with other strategies.

Use therapy, exercise, and social connection. You can effectively manage your mood. Living with Parkinson’s is a journey. It has many challenges. But you don’t have to let this struggle define you. Bring it into the light. This is a crucial step. It helps you live well with Parkinson’s.

A New Ray of Hope: The LIGHT for PD Clinical Trial

For those looking for innovative, non-medication, non-invasive, and at-home approaches, there is promising research underway.

This study is the LIGHT for PD Trial, which is investigating the use of light therapy as a home-based treatment to potentially manage non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s.

This approach is being explored as a safe, accessible way to potentially improve mood by helping to regulate the body’s internal clock. The trial especially shows promising potential in addressing depression in Parkinson’s.

However, it is close to its end with only 40 last sign-ups left.

So, if you are interested in exploring new treatment options and participating in important research, we encourage you to speak with your doctor or search online for the “LIGHT for PD Clinical Trial” to learn more about the study and see if you might be eligible to participate.