Introduction

The tremor. The stiffness. The deliberate slowness of movement. These are the hallmarks often associated with Parkinson’s disease.

But what if these very same symptoms point to something else entirely?

This is the complex reality of Parkinsonism. It encompasses a range of conditions that mimic Parkinson’s disease, creating diagnostic challenges for even experienced clinicians.

While slowness (bradykinesia), rigidity, and resting tremor are key indicators, they are not exclusive to Parkinson’s disease.

This diagnostic overlap necessitates careful evaluation by a neurologist to distinguish between Parkinson’s disease and other forms of Parkinsonism.

What makes Parkinsonism particularly complex is its ability to mimic Parkinson’s disease, creating challenges in pinpointing the exact cause of symptoms.

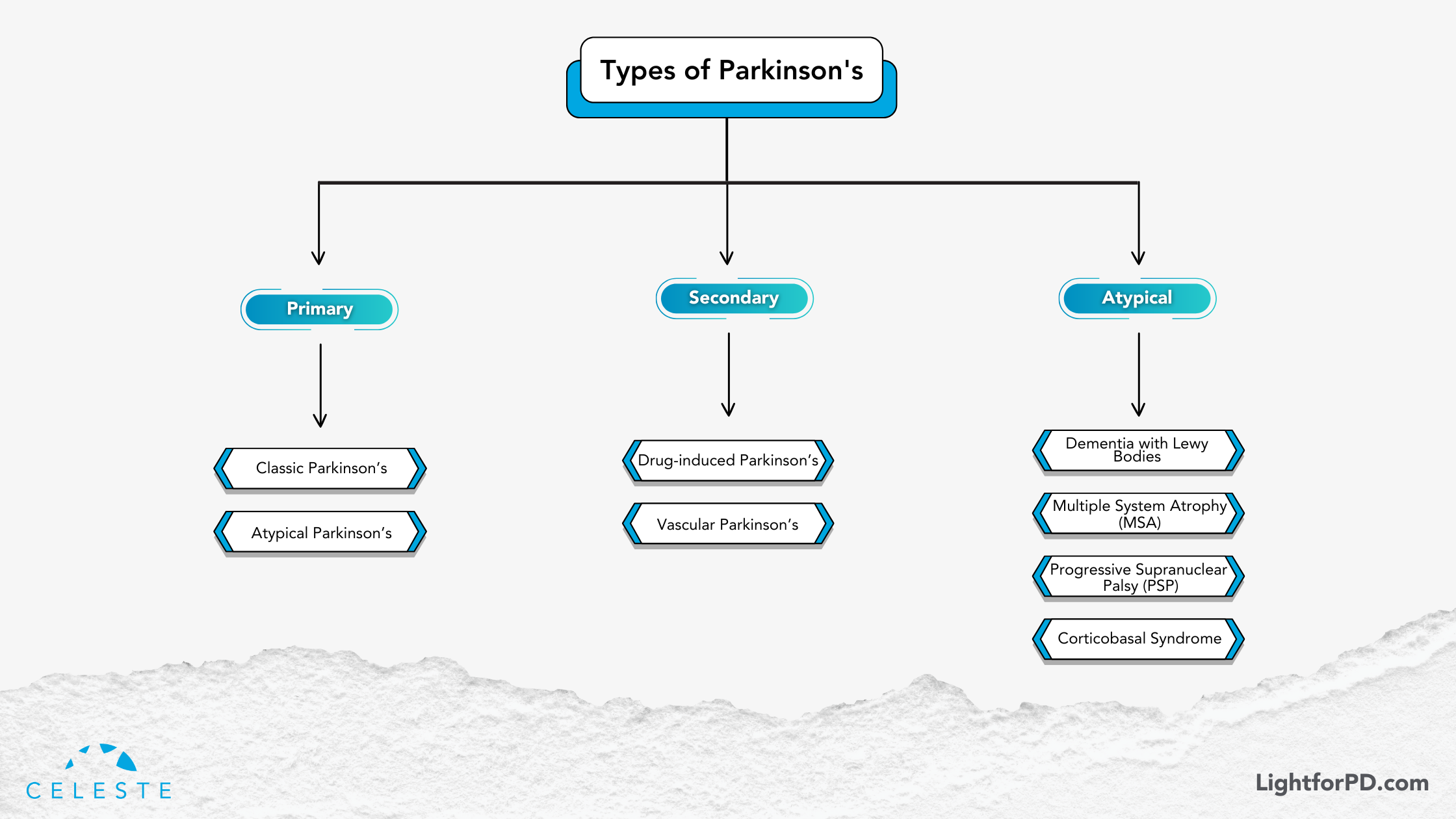

It’s important to understand that Parkinsonism is not a single disease but rather a spectrum of disorders categorized as primary and secondary.

In this blog, we’ll explore the most common conditions associated with Parkinsonian symptoms, shedding light on their differences and helping you navigate this intricate topic with greater clarity.

Whether you’re a patient, caregiver, or simply curious, this guide will give you a deeper understanding of the types of Parkinsonism and their unique characteristics.

Parkinsonism Classification

Parkinsonism is broadly categorized into two main types: primary and secondary. Let’s explore each in detail.

Primary Parkinsonism

Primary Parkinsonism refers to conditions where the underlying cause is a neurodegenerative process—a gradual decline in specific brain cells. This category includes PD itself, as well as a group of related disorders known as atypical Parkinsonian disorders.

Parkinson’s Disease (PD)

This is the most common form of Parkinsonism. It’s characterized by the progressive loss of dopamine-producing neurons in the brain. This leads to classic motor symptoms: tremors at rest, bradykinesia (slowness of movement), rigidity (stiffness), and postural instability (balance problems). PD typically responds well to levodopa, a medication that converts to dopamine in the brain, replenishing the depleted stores.

Atypical Parkinsonian Disorders

These conditions share some symptoms with PD but have distinct features and often respond differently to treatment. They include:

- Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB): This disorder is characterized by the presence of Lewy bodies (abnormal protein deposits) in the brain, similar to those found in PD but with a different distribution. In addition to motor symptoms, DLB is marked by fluctuating cognition, visual hallucinations, and REM sleep behavior disorder. Levodopa may offer some benefit for motor symptoms, but often less effectively than in PD, and can sometimes worsen psychiatric symptoms.

- Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP): PSP is characterized by early balance problems with frequent falls, difficulty with eye movements (especially looking downwards), rigidity in the neck and upper body, and cognitive changes. Unlike PD, tremor is usually not prominent in PSP. Levodopa typically provides minimal relief.

- Multiple System Atrophy (MSA): MSA is a rapidly progressive disorder affecting multiple systems in the body, including the autonomic nervous system (which controls involuntary functions like blood pressure and digestion), the cerebellum (which coordinates movement), and the basal ganglia (involved in motor control). Symptoms vary depending on the specific systems affected but can include parkinsonism, cerebellar ataxia (problems with balance and coordination), autonomic dysfunction (e.g., dizziness, bladder problems), and speech difficulties. Levodopa is generally not very effective in managing MSA.

- Corticobasal Degeneration (CBD): CBD is a rare disorder characterized by progressive motor and cognitive decline. Motor symptoms can include rigidity, dystonia (sustained muscle contractions), apraxia (difficulty with skilled movements), and alien limb phenomenon (involuntary movements of a limb). Cognitive changes can include problems with language, executive function, and visuospatial skills. Levodopa is usually not helpful in CBD.

Secondary Parkinsonism: When External Factors Play a Role

Secondary Parkinsonism arises from identifiable external factors, such as medications, toxins, or other medical conditions. Unlike primary Parkinsonism, the symptoms may be reversible if the underlying cause is addressed.

- Drug-Induced Parkinsonism: Certain medications, particularly antipsychotics, can block dopamine receptors in the brain, leading to Parkinsonian symptoms. These symptoms usually resolve when the medication is stopped.

- Vascular Parkinsonism: This type of Parkinsonism results from small strokes or other vascular problems in the brain that affect the areas responsible for motor control. Symptoms can be more variable than in PD and may include lower-body parkinsonism (affecting mainly the legs). Levodopa is typically not effective.

Other Secondary Causes: Other potential causes of secondary Parkinsonism include head trauma, infections, and exposure to certain toxins.

The Levodopa Response: A Key Differentiator

A crucial distinction between PD and many other forms of Parkinsonism is the response to levodopa. While PD typically shows a good initial response to this medication, atypical Parkinsonian disorders and secondary Parkinsonism often show little or no improvement. This difference can be a valuable clue for clinicians in making a diagnosis.

The Importance of Accurate Diagnosis

Differentiating between PD and other forms of Parkinsonism is essential because each condition has a different prognosis and requires tailored management strategies. A neurologist, especially one specializing in movement disorders, is best equipped to make an accurate diagnosis through a thorough neurological examination, medical history review, and sometimes brain imaging.

This information is intended for educational purposes and should not be considered medical advice. Always consult with a qualified healthcare professional for any health concerns or before making any decisions related to your health or treatment.

Diagnosing Parkinson’s Disease

Diagnosing Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a complex process. It’s a clinical puzzle that clinicians piece together using a combination of careful observation, detailed medical history, and neurological examination.

Unlike many other diseases, there is no single definitive test, such as a blood test or brain scan, that confirms a PD diagnosis.

The absence of a “gold standard” biomarker requires diagnosis to focus on motor symptoms while excluding similar conditions.

This clinical diagnostic approach can present challenges, especially in the early disease stages when symptoms are subtle or overlap with other conditions.

This reliance on clinical observation has driven the development and refinement of diagnostic criteria over time.

Evolving Diagnostic Standards

Historically, diagnostic criteria like those from the U.K.’s Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank provided a framework for clinicians.

However, our understanding of PD has evolved significantly, leading to the adoption of newer, more refined criteria from the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society.

These updated standards reflect the latest research and clinical insights, aiming to improve diagnostic accuracy and enable earlier intervention.

The core motor symptoms clinicians look for include: resting tremor (a trembling that occurs when the limb is at rest), bradykinesia (slowness of movement), rigidity (muscle stiffness), and postural instability (balance problems).

These cardinal features, when present in combination and carefully assessed, form the cornerstone of a PD diagnosis.

Beyond the Motor Symptoms: Exploring Prodromal Markers and Advanced Imaging

While motor symptoms are central to diagnosis, researchers are increasingly recognizing the importance of non-motor symptoms. These symptoms are often referred to as prodromal markers, which can precede the onset of motor difficulties by years.

These subtle clues, such as loss of smell (anosmia), REM sleep behavior disorder (acting out dreams), constipation, and mood changes like depression or anxiety, are being investigated as potential early indicators of PD risk.

Additionally, while not diagnostic on their own, advanced imaging techniques like the DaTscan can provide valuable supporting evidence. The DaTscan uses a radioactive tracer to visualize dopamine transporter activity in the brain. It helps to differentiate PD from other conditions with similar motor presentations.

This technology allows clinicians to see if the reduction in dopamine transporter activity is consistent with PD, further strengthening the diagnostic picture.

Ongoing research into biomarkers holds the promise of even earlier and more precise diagnostic tools in the future. This will potentially allow for earlier interventions to slow disease progression.

A Brighter Future: Exploring Light Therapy for Non-Motor Symptoms

Beyond the motor challenges of Parkinson’s, non-motor symptoms such as sleep disturbances, mood disorders, and fatigue can significantly impact quality of life. As research advances in diagnosing Parkinson’s, innovative approaches are also emerging to help manage the condition’s impact.

For instance, Light for PD (our ongoing Parkinson’s clinical trial) is exploring the benefits of light therapy for managing non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s. This non-invasive, at-home therapy offers a promising option to improve the quality of life for those living with PD. By targeting symptoms such as sleep disturbances and mood changes, Light for PD provides a gentle, science-backed way to complement existing treatment plans. If you or someone you know is navigating Parkinson’s, consider joining this trial to explore a new pathway to relief.

For more information to check your eligibility, visit www.lightforpd.com.