Introduction

Imagine waking up after a full night’s sleep, yet feeling as though you haven’t slept in days. Your limbs feel heavy, as if you are moving through molasses, and the mental effort required to simply plan your day feels akin to solving complex calculus.

This is not the “tiredness” that follows a long day of work or a rigorous gym session. This is Parkinson’s disease (PD) fatigue—a symptom that is as enigmatic as it is debilitating.

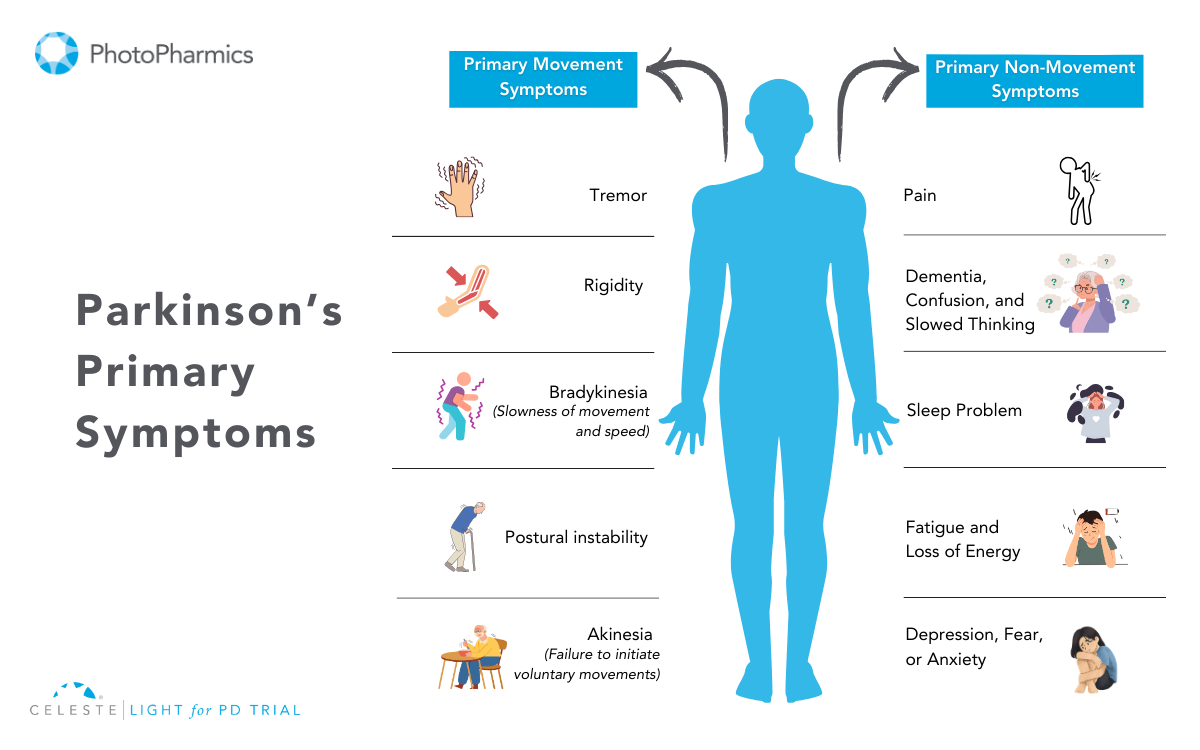

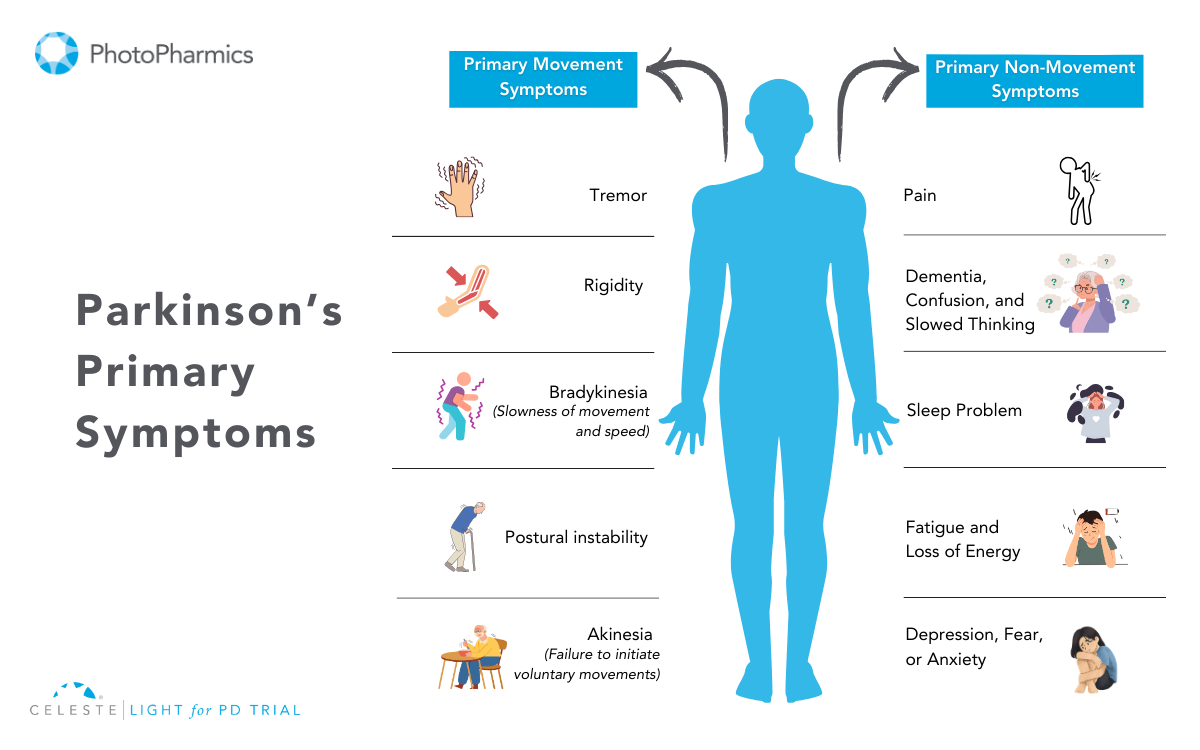

For decades, the public focus on Parkinson’s has centered on the visible motor symptoms: the tremors, the stiffness, and the shuffling gait.

However, for those living with the condition, the reality is often quite different. Studies consistently show that fatigue affects between 33% and 81% of patients, with nearly one-third citing it as their single most disabling symptom. It is an overwhelming sense of exhaustion that encompasses both physical and mental domains, often disproportionate to the activity undertaken and frequently unalleviated by rest.

Crucially, fatigue is not a sign of laziness, depression, or a simple lack of sleep. It is a primary physiological manifestation of the disease itself—a signal that the neurodegenerative process is affecting networks far beyond those that control movement.

By peeling back the layers of neurobiology, inflammation, and metabolic failure, we can begin to validate this invisible struggle and, more importantly, find strategic ways to manage it. This article explores the deep science behind why fatigue occurs and offers evidence-based strategies to reclaim your energy.

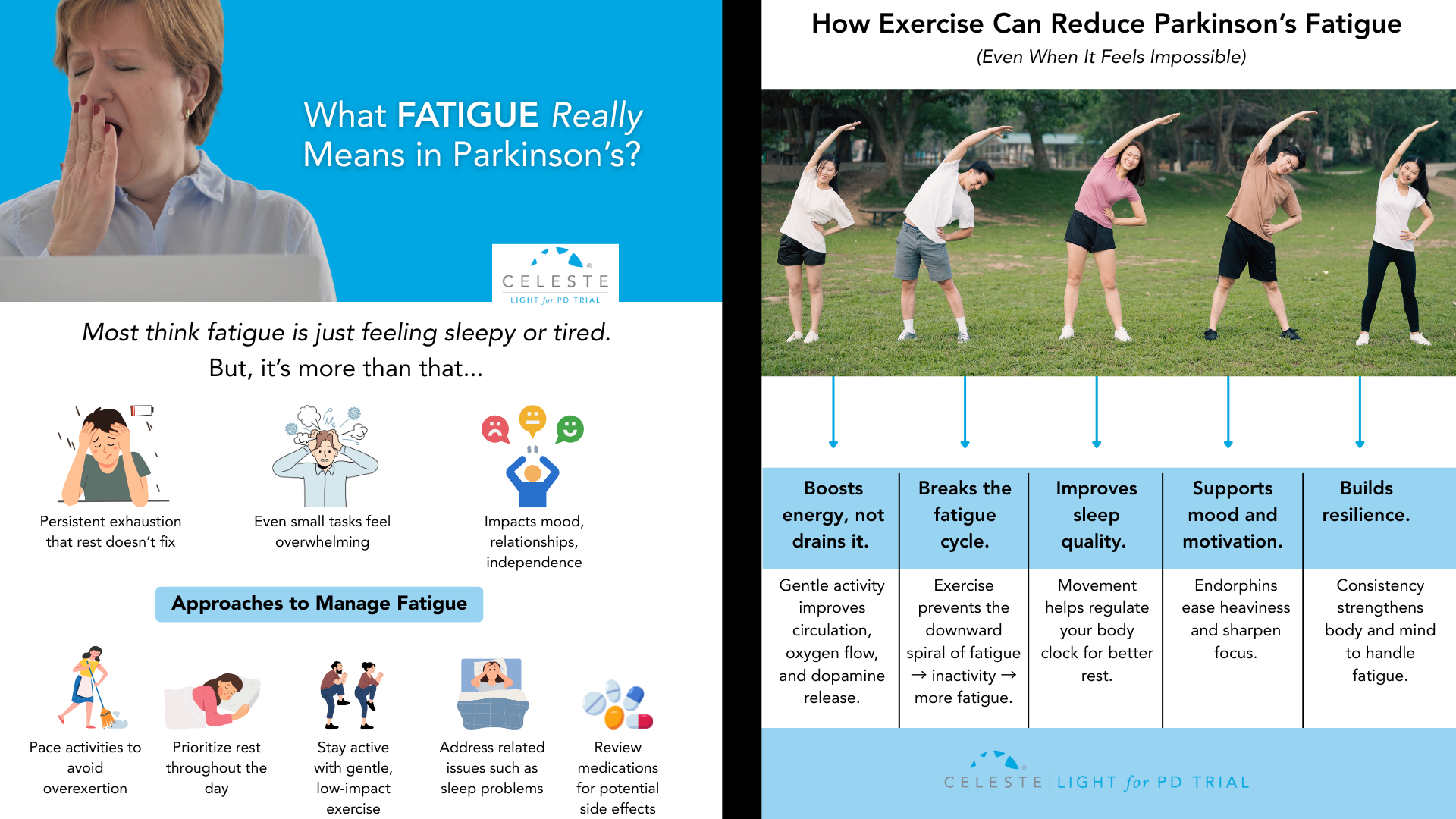

Fatigue: More Than Just Being “Tired”

To manage fatigue, we must first define it accurately. In the clinical landscape of Parkinson’s, fatigue is a distinct entity, separate from sleepiness (somnolence) or a lack of interest (apathy), though they often overlap.

Fatigue in PD is multidimensional. Patients often describe a “failure to initiate”—a sensation where the brain knows what to do, but the body simply cannot muster the energy to execute the command. This is known as Subjective Fatigue. It is a central sensation, a perception of weariness that acts as a heavy cloak over daily life.

Interestingly, this internal feeling doesn’t always match muscle performance. You might feel too weak to walk, but your muscles are physiologically capable of the task.

Contrast this with Objective Fatigability, which is a measurable decline in performance. In PD, this is “peripheral” fatigability. If you were to perform a repetitive motion, your force generation would decline more rapidly than that of a healthy person. This creates a frustrating disconnect: a central nervous system that struggles to drive the muscle, combined with muscles that tire too quickly.

Furthermore, the fatigue is pleiotropic, meaning it affects multiple systems. There is Physical Fatigue, characterized by muscle weakness and kinetic exhaustion, and Mental Fatigue, a difficulty in sustaining attention or concentration.

The latter is particularly intrusive, making tasks that require executive function—like balancing a checkbook or following a conversation—feel like climbing a mountain.

Understanding these distinctions is the first step toward targeted management.

The Science Behind Fatigue in Parkinson’s

Why does the brain stop generating energy?

One of the most compelling neurobiological theories is the Effort-Reward Imbalance Hypothesis.

Every action we take, from reaching for a coffee cup to walking to the mailbox, involves a split-second calculation by the brain: Is the reward of this action worth the effort required to achieve it? This calculation relies heavily on dopamine, particularly in the mesolimbic system—the brain’s reward center.

In Parkinson’s, the degeneration of dopamine-producing neurons isn’t limited to the areas controlling movement (the nigrostriatal pathway). It extends to the ventral tegmental area, which projects to the nucleus accumbens. When dopamine is depleted here, the brain’s “currency converter” breaks down.

The result is a skewed cost-benefit analysis. The brain begins to inflate the perceived “cost” (effort) of an action while diminishing the perceived “value” of the reward. To the PD brain, walking to the kitchen might “cost” as much energy as running a mile, while the reward of getting a glass of water feels negligible.

Consequently, the sensation of fatigue acts as a behavioral “stop signal.” It is the brain’s misguided attempt to conserve energy because it calculates that the exertion isn’t justified. This “central activation deficit” means patients have to exert massive mental willpower to override this stop signal, leading to profound exhaustion.

Additionally, this isn’t just about dopamine. Serotonin, the neurotransmitter regulating mood and sleep, plays a massive role. Serotonergic neurons in the brainstem often degenerate before dopamine neurons. PET scan studies reveal that fatigued PD patients have significantly reduced serotonin transporter availability in the limbic system.

This explains why fatigue often persists even when patients are perfectly medicated with Levodopa—the dopaminergic deficit is treated, but the serotonergic “non-dopaminergic” fatigue remains.

Inflammation and “Sickness Behavior”

While the brain struggles with neurotransmitters, the body is fighting its own battle. Emerging research supports a “whole-body” view of PD fatigue, suggesting it mimics “sickness behavior”—the lethargy you feel when you have the flu.

Parkinson’s is increasingly viewed as a state of chronic, low-grade inflammation. Patients often exhibit elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, specifically Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-alpha). These inflammatory messengers don’t just stay in the blood; they cross the blood-brain barrier and activate microglia, the brain’s immune cells.

When microglia are activated, they release reactive oxygen species and more cytokines, creating a toxic, inflammatory environment that impairs neural signaling. This biological state signals the body to withdraw, rest, and conserve energy to “fight” an infection that isn’t actually there.

A key player in this process is the NLRP3 inflammasome, an intracellular alarm system. In a healthy brain, dopamine inhibits this alarm. But in PD, as dopamine levels fall, the “brake” on the immune system is removed. The NLRP3 inflammasome becomes hyperactive, churning out inflammatory signals that drive fatigue.

Simultaneously, there is a crisis in the cellular power plants: the mitochondria. A systemic reduction in Complex I activity of the mitochondrial electron transport chain is a robust finding in PD. This means the cells are literally less efficient at producing ATP, the energy currency of life. This bioenergetic failure is systemic, found in skeletal muscles as well as the brain, explaining why physical endurance is so compromised.

Factors Contributing to Fatigue

If neurodegeneration and inflammation are the core of the onion, secondary comorbidities are the outer layers. These are often the most treatable aspects of fatigue, yet they frequently go diagnosing.

Sleep Pathology is ubiquitous. It’s not just about getting eight hours; it’s about the quality of that sleep. Many PD patients suffer from Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) or REM Sleep Behavior Disorder (RBD), where they physically act out dreams. This fragmentation prevents restorative sleep, leaving the brain in a permanent state of debt.

Autonomic Dysfunction is another silent thief of energy. Many patients experience Neurogenic Orthostatic Hypotension (nOH)—a drop in blood pressure upon standing. This happens because the autonomic nervous system fails to release enough norepinephrine to constrict blood vessels. The result is chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Even if you don’t faint, your brain is getting slightly less oxygen than it needs whenever you are upright. This manifests as “brain fog,” visual blurring, and a coat-hanger ache in the neck and shoulders—all perceived as profound tiredness.

Finally, we must address Neuropsychiatric Factors. While depression and fatigue are distinct, they feed into each other. Depression can rob a patient of motivation (anhedonia), while apathy—a lack of interest separate from sadness—can mimic the “effort-reward” failure of fatigue. Distinguishing these requires careful clinical assessment, as the treatment for depression (SSRIs/SNRIs) differs from the treatment for pure fatigue or apathy.

Pharmacological Management: Consult Your Doctor

When it comes to treating fatigue with medication, the landscape is complex and highly individualized. There are numerous pharmaceutical options available today that target different aspects of fatigue—whether it stems from dopamine deficiency, excessive daytime sleepiness, or other underlying chemical imbalances.

However, because fatigue in Parkinson’s is so multifaceted—involving everything from neurotransmitters to blood pressure regulation—no single drug works for everyone.

What provides energy for one patient might cause side effects in another.

Therefore, it is absolutely essential to have a detailed conversation with your neurologist or movement disorder specialist. They can help identify the specific type of fatigue you are experiencing and tailor a treatment plan that is safe and effective for your unique medical profile.

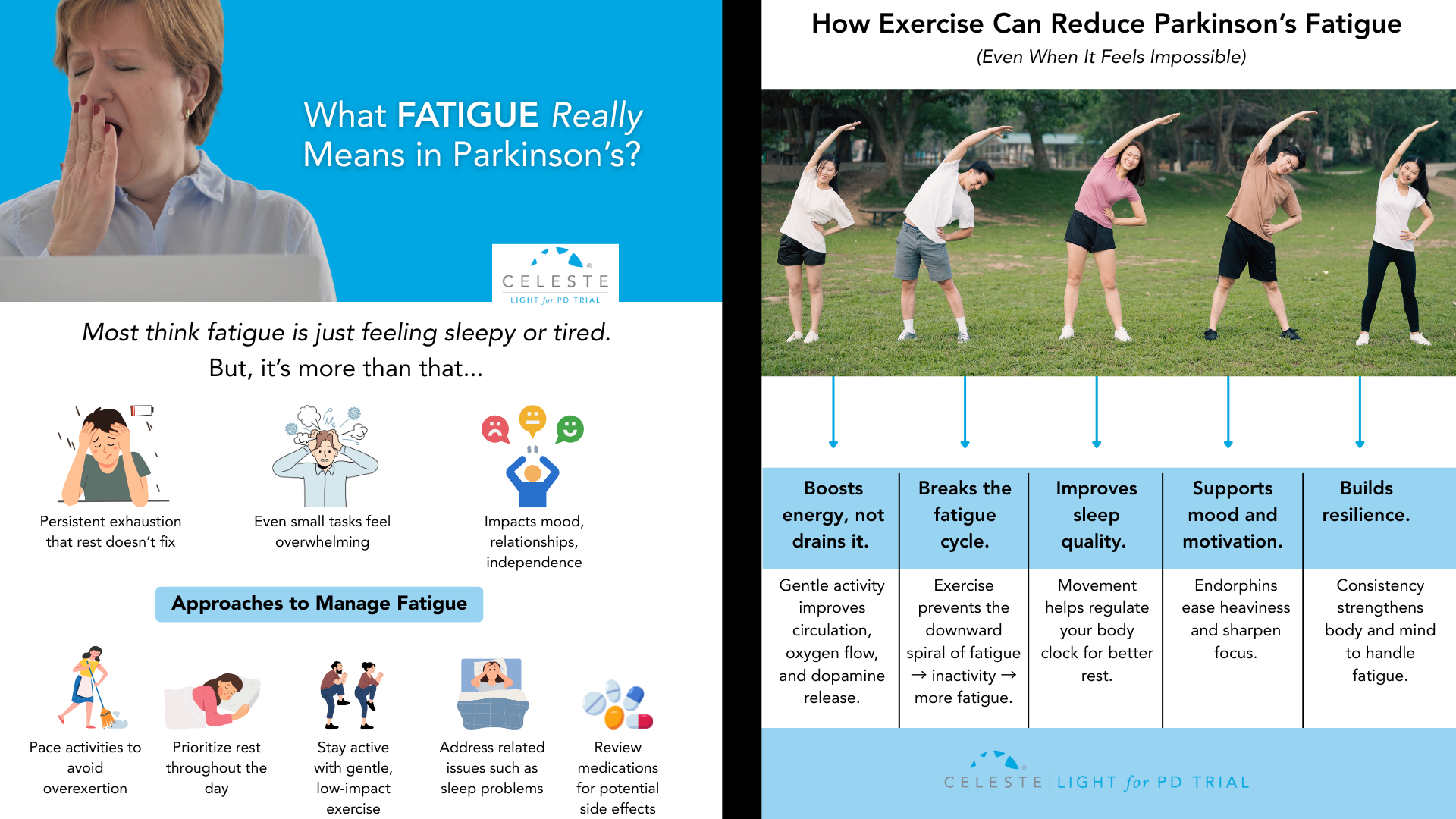

Exercise: The Only Disease-Modifying Strategy?

While pills treat symptoms, exercise may actually change the biology of the fatigued brain. It is arguably the most robust intervention available.

Aerobic Training is critical. Regular cardiovascular exercise (walking, cycling, swimming) does more than just strengthen the heart; it lowers the resting levels of those pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6) that drive sickness behavior. It also improves oxygen delivery to the mitochondria, helping to mitigate the bioenergetic failure.

However, intensity matters. Emerging research on High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) suggests that pushing your heart rate to 60-80% of its reserve triggers the release of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF). BDNF acts like fertilizer for the brain, promoting synaptic plasticity in the basal ganglia. High-intensity work has also been shown to normalize “cortical silent periods”—essentially resetting the excitability of the motor cortex.

Resistance Training is the other half of the equation. By increasing muscle strength, you lower the relative effort required for daily tasks. If your legs are stronger, standing up from a chair takes 30% of your maximum effort instead of 80%, leaving you with more energy in the tank for the rest of the day.

The recommended prescription is a mix: at least 3 days a week of aerobic activity combined with resistance training, totaling 30-40 minutes per session.

Diet and Lifestyle Management

Finally, management extends to how you fuel your body and how you spend your energy budget.

From a dietary perspective, metabolic therapies are gaining traction. A randomized trial comparing a Mediterranean diet to a Ketogenic diet found that while both improved health, the Ketogenic group (high fat, low carb) saw significantly greater improvements in non-motor symptoms like fatigue.

The theory is that ketone bodies can bypass the defective Complex I in the mitochondria, providing an alternative, more efficient fuel source for neurons. While a strict Keto diet is hard to maintain, moving toward a lower-carb, healthy-fat diet may offer benefits.

Fatigue in Parkinson’s is a heavy burden, impacting not just the patient but the entire family unit. It limits social interaction and increases caregiver strain.

But by recognizing it as a physiological storm—of inflammation, neurochemistry, and metabolism—we can stop blaming ourselves and start managing our biology.

Through a combination of smart medication, high-intensity movement, and strategic energy budgeting, vitality is not a thing of the past.

Understanding Parkinson’s is a journey of continuous discovery. To stay updated on the latest news, insightful information, and updates regarding Parkinson’s research and management follow @photopharmics_ on social media.

Introduction

Did you know that unintentional weight loss and nutritional deficiencies are among the most common challenges for people with Parkinson’s disease, often occurring even before a diagnosis is made?

In simple terms, Parkinson’s Disease is a condition where the specific brain cells responsible for controlling movement gradually stop working. These cells are supposed to produce a chemical called dopamine, which your body needs to send smooth signals to your muscles. When these cells break down over time, the brain has less dopamine to work with, leading to symptoms like tremors, stiffness, and slowness.

While there is currently no specific “Parkinson’s Diet” that can cure the condition, what you eat pr the nutrition you take plays a fundamental role in your overall treatment plan. Food is not just fuel; it consists of chemical compounds that interact with your medication, support your brain cells, and help manage the specific symptoms that affect your daily quality of life.

Understanding nutrition offers a sense of control. You cannot always predict how your symptoms will fluctuate day-to-day, but you can control what you put on your plate. This guide breaks down the essential nutrients and dietary strategies that can help you feel your best while living with Parkinson’s.

The Protein-Medication Balance

If you take levodopa (found in medications like Sinemet), understanding protein is perhaps the most critical part of your nutrition education.

Levodopa is a protein-building block (an amino acid). For it to work, it must travel from your stomach, into your blood, and cross into your brain. The challenge is that dietary protein—from meat, dairy, eggs, and beans—uses the exact same transportation system to get into the brain.

When you eat a high-protein meal at the same time you take your medication, the protein saturates the transporters. This acts like a traffic jam, preventing your medication from getting where it needs to go. This can lead to:

- A delay in the medication kicking in (“delayed ON”).

- The medication wearing off sooner than expected (“wearing off”).

Practical Strategy: You do not need to stop eating protein; it is vital for maintaining muscle strength. Instead, focus on timing:

- The 30-Minute Rule: Aim to take your medication at least 30 minutes before a meal or 60 minutes after a meal. This gives the drug a head start to reach the brain before the food arrives.

- Protein Redistribution: If you experience significant fluctuations in your symptoms, talk to your doctor about shifting your main protein intake to the evening meal. You might eat lighter, plant-based meals for breakfast and lunch (like oatmeal or vegetable soup) and save your chicken, fish, or meat for dinner. This ensures your medication works best during the active hours of the day.

Antioxidants: Protecting Your Cells

Parkinson’s disease involves a process called oxidative stress, which can damage brain cells over time. Think of it like rust forming on metal. Antioxidants are nutrients that help clear out the “rust” and protect cells from damage.

Research suggests that distinct nutrition strategies focusing on antioxidants may support overall brain health. The best way to get these is through colorful fruits and vegetables.

Key Nutrients to Focus On:

- Vitamin C: Found in citrus fruits, bell peppers, strawberries, and broccoli.

- Vitamin E: Found in nuts (especially almonds), seeds, spinach, and wheat germ.

- Flavonoids: These are powerful compounds found in deeply colored plants. Berries (blueberries, raspberries, blackberries) are particularly rich in flavonoids and have been linked to slower rates of cognitive decline in older adults.

Practical Strategy: Aim to “eat the rainbow.” Try to include a fruit or vegetable of a different color at every meal. For example, add berries to your morning cereal, have a leafy green salad at lunch, and include roasted carrots or peppers with dinner.

Healthy Fats and Omega-3s

The human brain is approximately 60% fat, so the type of fat you eat matters. While saturated fats (found in fried foods and processed meats) should be limited, unsaturated fats are essential for brain function and heart health.

Omega-3 fatty acids are a specific type of healthy fat that is anti-inflammatory. Since inflammation is a component of Parkinson’s, consuming adequate Omega-3s is a smart nutritional move.

Best Sources:

- Fatty Fish: Salmon, mackerel, sardines, and trout are excellent sources. Aim for two servings a week.

- Plant Sources: Walnuts, flaxseeds, chia seeds, and hemp seeds.

- Cooking Oils: Olive oil is a staple of the Mediterranean diet and is an excellent choice for cooking and dressing salads.

Practical Strategy: Swap out butter or margarine for olive oil when cooking. Snack on a handful of walnuts instead of chips. If you do not eat fish, ask your doctor if an Omega-3 supplement is right for you.

Fiber and Fluids: Managing Constipation

Constipation is one of the most common non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s. It happens because the disease can slow down the movement of muscles in the digestive tract. Not only is it uncomfortable, but severe constipation can also interfere with the absorption of your medication, making it less effective.

Diet or nutrition is your first line of defense against this symptom.

The Fiber Factor: Fiber adds bulk to the stool and helps it move through the intestines.

- Whole Grains: Oats, brown rice, quinoa, and whole-wheat bread.

- Legumes: Lentils, chickpeas, and black beans.

- Fruits and Veggies: Apples (with skin), pears, prunes, and leafy greens.

The Hydration Equation: Fiber acts like a sponge—it needs water to work. If you increase fiber without increasing water, it can actually make constipation worse.

- Water Goal: Aim for 6 to 8 glasses of water a day unless your doctor has restricted your fluid intake.

- Hydrating Foods: Cucumbers, watermelon, and soups also count toward your fluid intake.

Practical Strategy: Start your day with a glass of warm water or tea. The warmth can stimulate digestion. Increase your fiber intake gradually over several weeks to prevent bloating.

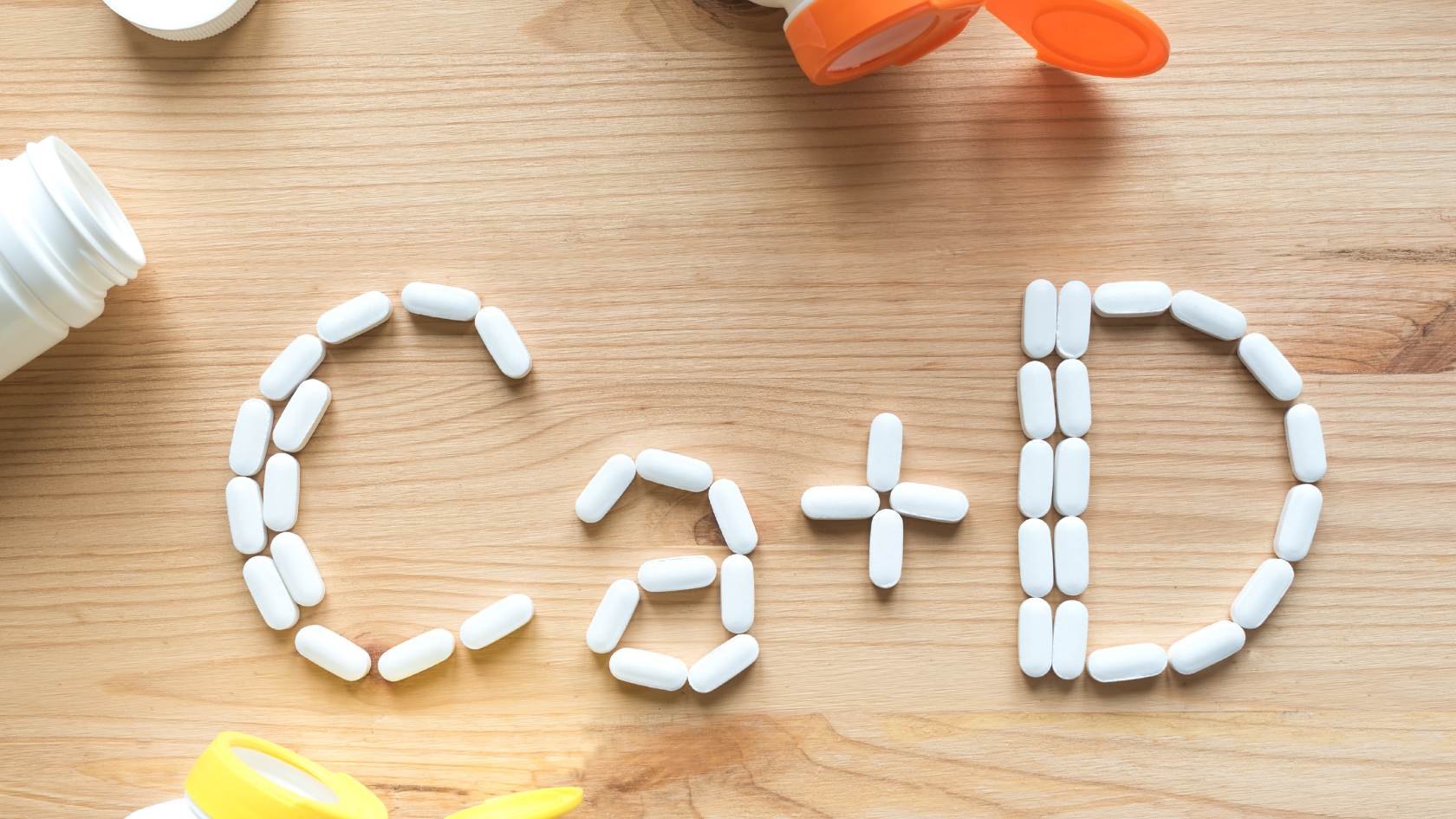

Bone Health Nutrients: Calcium and Vitamin D

People with Parkinson’s are at a higher risk of falls due to balance issues. Consequently, prioritizing nutrition for strong bones is critical to prevent fractures if a fall occurs.

Research shows that people with Parkinson’s are often deficient in Vitamin D. This vitamin is essential because it helps your body absorb calcium.

Key Sources:

- Calcium: Dairy products (milk, yogurt, cheese), fortified plant milks (almond or soy milk), tofu, and dark leafy greens like kale and collard greens.

- Vitamin D: Fatty fish, egg yolks, and fortified foods. However, it is difficult to get enough Vitamin D from food alone. Your body makes it from sunlight, but many people require a supplement to reach optimal levels.

Practical Strategy: Have your Vitamin D levels checked by your doctor. If you are avoiding dairy, make sure you are choosing calcium-fortified alternatives.

Magnesium for Muscle Health

Magnesium is a mineral that plays a role in muscle relaxation and nerve function. Some people with Parkinson’s suffer from painful muscle cramps or “dystonia,” particularly at night or in the early morning. While magnesium isn’t a cure-all, ensuring you have adequate levels through nutrition may help support smoother muscle function.

Best Sources:

- Spinach and Swiss chard

- Pumpkin seeds and almonds

- Black beans

- Avocados

- Dark chocolate (in moderation)

B Vitamins and Homocysteine

Levodopa medication can sometimes lead to an increase in a compound called homocysteine in the blood. Elevated homocysteine levels are associated with a higher risk of heart disease and potential cognitive issues.

To break down homocysteine, the body needs B vitamins—specifically Vitamin B12, Vitamin B6, and Folate (B9).

Best Sources:

- Vitamin B12: Found primarily in animal products like meat, fish, eggs, and dairy. If you are a vegetarian or vegan, you may need a supplement.

- Folate: Found in dark green leafy vegetables, beans, peas, and fortified cereals.

- Vitamin B6: Found in chickpeas, potatoes, bananas, and poultry.

Practical Strategy: A balanced diet usually provides enough B vitamins, but your doctor can check your levels with a simple blood test to see if you need additional support.

Summary

Nutrition for Parkinson’s isn’t about strict rules or deprivation. It is about adding value to your meals. By focusing on whole, nutrient-dense foods, you are providing your brain and body with the resources they need to function efficiently.

Small changes, like drinking an extra glass of water or swapping white bread for whole wheat, can add up to significant improvements in how you feel day-to-day.

Stay informed on Parkinson’s management. For more helpful articles on lifestyle, light therapy, and wellness for Parkinson’s disease, follow PhotoPharmics on social media and visit our blog at photopharmics.com.

Introduction

Receiving a Parkinson’s disease diagnosis is a life-altering moment.

When that moment comes decades earlier than expected—sometime between the ages of 21 and 50—it brings a unique set of questions, challenges, and emotions.

A Young-Onset Parkinson’s Disease (YOPD) diagnosis forces a head-on collision with questions you never expected to ask so soon. It’s a profound interruption, challenging your identity, your plans, and your vision for the decades ahead.

But while the initial shock can feel isolating and overwhelming, it does not have to be defining. A diagnosis is not a conclusion; it is a turning point. It is the beginning of a journey where you learn to navigate, adapt, and take control.

This guide is for that journey. It’s not a story about limitations, but a roadmap for resilience, offering a proactive strategy to manage the disease and live a full, meaningful, and empowered life.

The Celeste (Light for PD) trial is showing promising results with a non-invasive approach to managing depression and other symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Early findings suggest improved emotional well-being and quality of life for participants. Learn more about the study and how you can get involved.

What is Young-Onset Parkinson’s (YOPD) and How is it Different?

At its core, YOPD shares the same biology as its late-onset counterpart: the progressive loss of dopamine-producing cells in the brain.

Dopamine is a crucial chemical messenger that helps control movement, so this loss leads to the hallmark motor symptoms of Parkinson’s. However, the way the disease unfolds can be quite different.

One of the most significant differences is the rate of progression, which is typically much slower in YOPD.

People diagnosed at a younger age often remain independent and cognitively sharp for a longer period. But here lies a key paradox: because you live with the disease longer, you are exposed to medications for more years.

This leads to a higher and earlier likelihood of developing treatment-related complications like dyskinesia (involuntary movements) and motor fluctuations (“on-off” periods). This paradox shapes the entire treatment strategy from day one.

Here’s a quick comparison:

- Slower Progression: YOPD generally progresses more slowly, especially concerning cognitive decline and balance issues.

- Different Early Symptoms: YOPD often begins with dystonia (painful muscle cramping, like a foot turning inward) and rigidity, whereas late-onset PD more frequently starts with tremor and balance problems.

- Earlier Treatment Complications: People with YOPD tend to develop dyskinesias and “on-off” fluctuations sooner in response to the gold-standard medication, levodopa.

- Stronger Genetic Link: While most Parkinson’s is not directly inherited, genetics plays a much larger role in YOPD. A significant percentage of those diagnosed under 50, and especially under 30, have an identifiable genetic link.

Recognizing the Symptoms of Young-Onset Parkinson’s

Parkinson’s is widely perceived as a disease of the elderly, which is why the path to a YOPD diagnosis can be long and frustrating.

Many people spend years on a “diagnostic odyssey,” with early symptoms being misdiagnosed as sports injuries, carpal tunnel syndrome, a “frozen shoulder,” or simply stress. Understanding the wide range of symptoms is key.

Motor Symptoms

While a resting tremor is a classic sign, it’s not always the first or most prominent one in YOPD. Look out for:

- Dystonia: As mentioned, this is a hallmark of YOPD. It can be a painful, sustained twisting or cramping in a limb, often a foot or hand.

- Rigidity: A stiffness in the arms, legs, or trunk that can be painful and limit your range of motion.

- Bradykinesia: This is a generalized slowness of movement that makes everyday tasks, like buttoning a shirt or writing, feel difficult and cumbersome.

- Tremor: Often starts in one hand at rest. In YOPD, it can sometimes be faster than the classic “pill-rolling” tremor.

The Invisible Burden: Non-Motor Symptoms

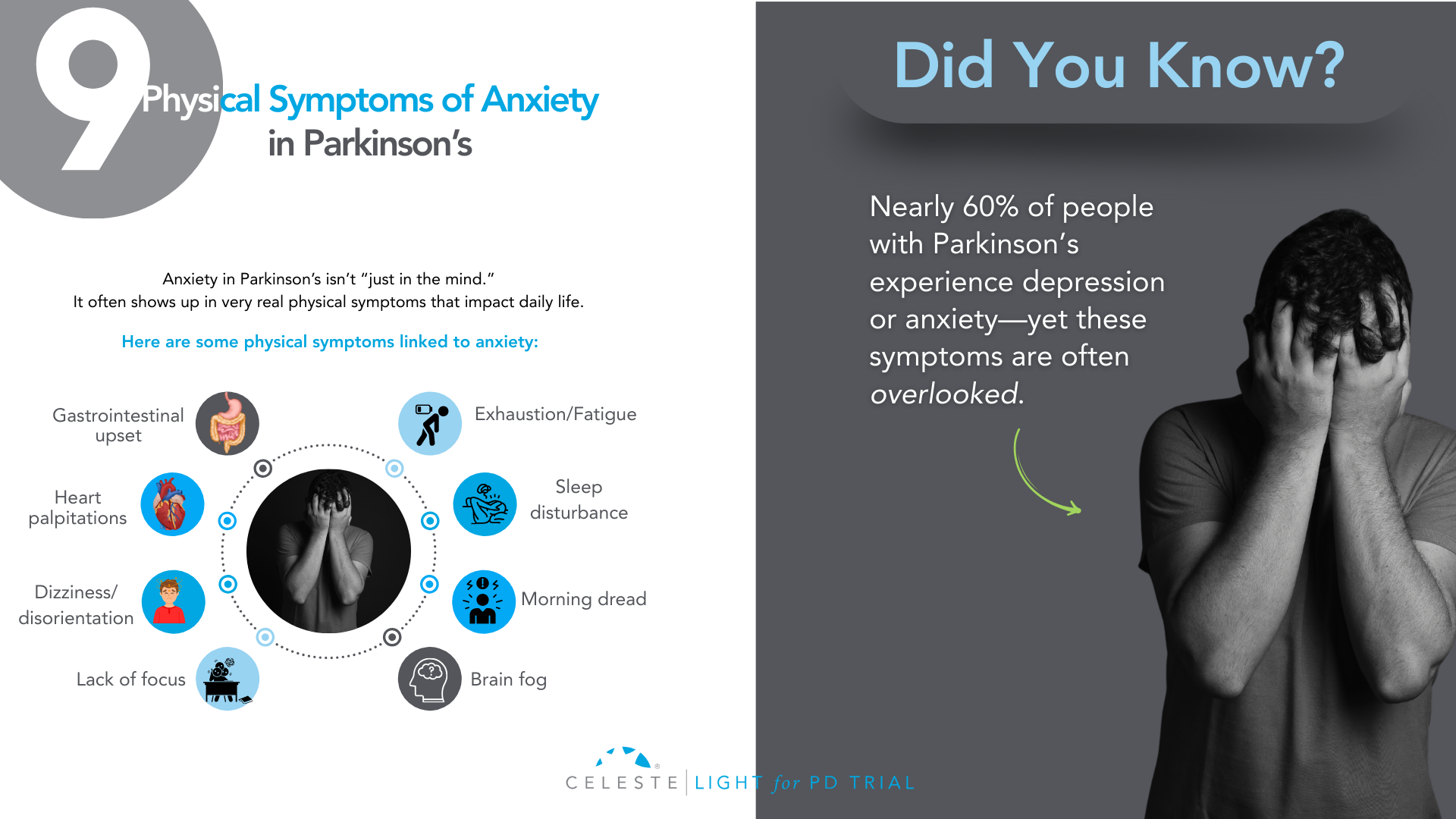

Often, the non-motor symptoms of YOPD can be more disruptive than the physical ones. They are a direct result of the same brain changes and are not just a reaction to the diagnosis.

- Depression and Anxiety: These are incredibly common and are considered an intrinsic part of the disease itself. They deserve to be treated as seriously as any motor symptom.

- Fatigue: A profound, debilitating sense of exhaustion that isn’t relieved by sleep.

- Sleep Problems: Insomnia and REM Sleep Behavior Disorder (physically acting out dreams) are frequent issues.

- Cognitive Changes: While severe dementia is rare in YOPD, you might notice more subtle difficulties with planning, multitasking, and problem-solving.

- Other common issues include loss of smell, constipation, and pain or tingling sensations.

The Genetic Puzzle of Young-Onset Parkinson’s

For many living with YOPD, the question “Why me?” quickly leads to “Is this genetic?”

The answer is complex, but the link is undeniable.

While the vast majority of Parkinson’s cases are idiopathic (meaning they have no known cause), a much larger percentage of YOPD cases are tied to specific genetic mutations. If you were diagnosed under 40, there’s a significant chance your condition has a genetic component.

Key genes associated with Parkinson’s include:

- PRKN (Parkin): Mutations in this gene are one of the most common causes of YOPD. It typically leads to a very slow-progressing form of the disease.

- PINK1 and DJ-1: Similar to PRKN, these genes are associated with early-onset, slow-progressing Parkinson’s.

- LRRK2 (Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2): This is the most common genetic contributor to late-onset Parkinson’s, but can also cause YOPD.

Genetic testing can provide clarity, help you understand potential risks for family members, and may qualify you for specific clinical trials targeting these genetic pathways. A conversation with a genetic counselor is the best first step to explore this option.

The Celeste (Light for PD) trial is showing promising results with a non-invasive approach to managing depression and other symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Early findings suggest improved emotional well-being and quality of life for participants. Learn more about the study and how you can get involved.

Building Your Proactive YOPD Treatment Plan

Managing YOPD is a marathon, not a sprint. The goal is to balance effective symptom control now with preserving quality of life for the future. This requires a dynamic partnership with a multidisciplinary care team.

The “Levodopa Dilemma” and First-Line Therapies

Carbidopa/levodopa is the most powerful drug for PD symptoms. However, due to the high risk of developing motor complications, the strategy in YOPD is often to delay its use for as long as possible. To do this, doctors often start with other medications:

- Dopamine Agonists: These drugs mimic dopamine in the brain. They are effective but carry a significant risk of side effects, most notably Impulse Control Disorders (ICDs), such as compulsive gambling or shopping. This requires vigilant monitoring and open communication with your family and doctor.

- MAO-B Inhibitors: These medications provide a modest symptom benefit by helping the brain preserve its own dopamine. They are generally well-tolerated.

Eventually, levodopa will become necessary. At that point, the focus shifts to carefully managing doses and timing to keep you functioning well while minimizing side effects.

Advanced Therapies: A Strategic Move

For those whose motor fluctuations become difficult to manage with oral medications, advanced therapies are not a last resort but a proactive step to restore function.

- Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS): This surgical procedure acts like a “pacemaker for the brain,” using implanted electrodes to regulate the abnormal brain signals causing motor symptoms. For a person in their 40s or 50s, DBS can provide many years of improved function during peak career and family-raising years.

- Infusion Therapies: For severe fluctuations, continuous drug delivery via a small, wearable pump can provide a steady, reliable dose of medication throughout the day.

Lifestyle Management for Young-Onset Parkinson’s

Medical treatments are only one part of the equation. What you do every day can have a profound impact on your symptoms and overall well-being.

Exercise is Non-Negotiable

If there is one magic bullet in Parkinson’s care, it’s vigorous exercise. Research suggests it may even be neuroprotective, potentially slowing the disease’s progression. It helps your brain use dopamine more efficiently and builds new neural connections. Your goal should be to exercise with as much intensity as you can safely tolerate, as often as you can.

Build an “exercise cocktail” that includes:

- Aerobic Activity: Running, cycling, swimming, high-intensity interval training (HIIT).

- Strength Training: Using weights or resistance bands to combat muscle weakness.

- Mind-Body Practices: Non-contact boxing, dance (especially tango), Tai Chi, and yoga are fantastic for improving balance, agility, and coordination.

Nutrition for Brain Health

There’s no specific “Parkinson’s diet,” but a brain-healthy eating pattern can make a difference. The Mediterranean or MIND diets are highly recommended. They are rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, and healthy fats, which help fight inflammation and support cognitive function.

A crucial tip for those on levodopa: dietary protein can interfere with the medication’s absorption. Try taking your dose on an empty stomach (30-60 minutes before a meal) to maximize its effect.

Mental & Emotional Health: A Priority in YOPD Management

Depression and anxiety are not just reactions to a difficult diagnosis; they are clinical symptoms of Parkinson’s, caused by the same chemical changes in the brain that affect movement.

In YOPD, these non-motor symptoms can be particularly challenging, as you grapple with the disease’s impact on your career, finances, and family life. Prioritizing your mental health is as critical as managing your physical symptoms.

Strategies for emotional well-being include:

- Seek Professional Help: A therapist, counselor, or psychiatrist can provide invaluable tools for coping with the emotional toll of a chronic illness. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) can be particularly effective.

- Consider Medication: Antidepressants can be very effective and should be discussed with your neurologist or a psychiatrist.

- Practice Mindfulness: Techniques like meditation and deep-breathing exercises can help manage anxiety and ground you in the present moment.

- Stay Connected: Resist the urge to withdraw. Lean on your support system and maintain social connections that bring you joy and a sense of belonging. Open communication with your loved ones is essential.

The Celeste (Light for PD) trial is showing promising results with a non-invasive approach to managing depression and other symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Early findings suggest improved emotional well-being and quality of life for participants. Learn more about the study and how you can get involved.

Navigating Life, Work, and Relationships

A YOPD diagnosis forces you to re-evaluate everything. Open communication and proactive planning are your best tools.

Career and Disclosure

The decision to tell your employer is personal, but it’s a legal prerequisite for requesting workplace accommodations under laws like the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Consider disclosing before your symptoms affect your performance, allowing you to control the narrative. Simple accommodations can make a world of difference:

- For tremor: Voice recognition software, ergonomic keyboards.

- For fatigue: A flexible schedule, options to work from home.

- For slowness: Modified deadlines, a self-paced workload.

- For concentration: Noise-canceling headphones in an open office.

Family and Parenting

Explaining YOPD to children can be daunting, but it’s essential. Use simple, age-appropriate language to explain symptoms, reassure them that it’s not their fault and not contagious, and maintain as much routine and stability as possible. The goal is to build trust and prevent them from inventing scarier explanations for what they see.

In a partnership, roles may shift, which can be stressful. Honest, vulnerable communication is the key to navigating these changes together. Redefine intimacy, focusing on emotional closeness and adapting your physical relationship as needed.

Finding Your Community, Looking to the Future

You are not alone. A vast network of support and a vibrant research community are working to make life better and find a cure.

- Connect with Others: Find a YOPD-specific support group, either locally or online. Sharing experiences with peers who truly understand is invaluable.

- Lean on National Foundations: Organizations like The Michael J. Fox Foundation, the Parkinson’s Foundation, and the American Parkinson’s Disease Association (APDA) are incredible resources for information, finding clinical trials, and connecting with local support.

- Stay Hopeful: The research landscape is more promising than ever, with advances in biological markers (like the alpha-synuclein seed amplification assay), precision medicine targeting specific genes, and therapies aimed at slowing the disease.

A diagnosis of Young-Onset Parkinson’s is the start of a new chapter, not the end of the book. By arming yourself with knowledge, embracing a proactive lifestyle, building a strong support team, and connecting with your community, you can navigate this journey with resilience, hope, and a continued sense of purpose.

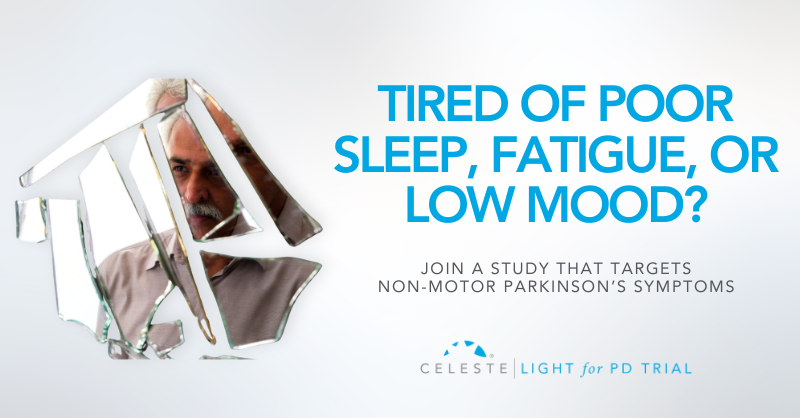

A Bright Spot in Research: Our “Light for PD” Trial

For many living with Parkinson’s, the associated depression can be as debilitating as any motor symptom. We are pioneering a non-invasive, drug-free approach to managing this specific challenge. In recognition of its promise, our light therapy device has received a “Breakthrough Device” designation from the FDA for its potential to help manage PD.

Our current Phase 3 clinical study, the “Light for PD” trial, is investigating whether this specialized light therapy can improve the motor and non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s. The trial has already shown a strong potential in managing depression associated with Parkinson’s.

Importantly, the trial is designed so that you can participate from the comfort of your own home, making it more accessible.

If you are interested in being part of the science that could change the future of Parkinson’s care, we encourage you to learn more about the “Light for PD” trial. You can discuss this opportunity with your neurologist or read all about it on our website to see if it might be a good fit for you.

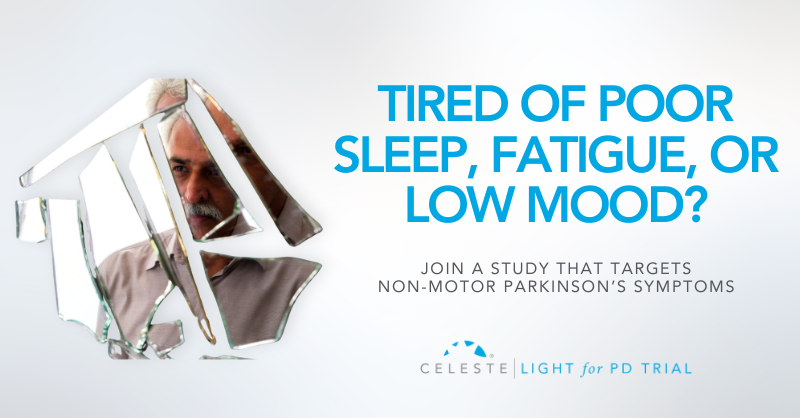

Introduction

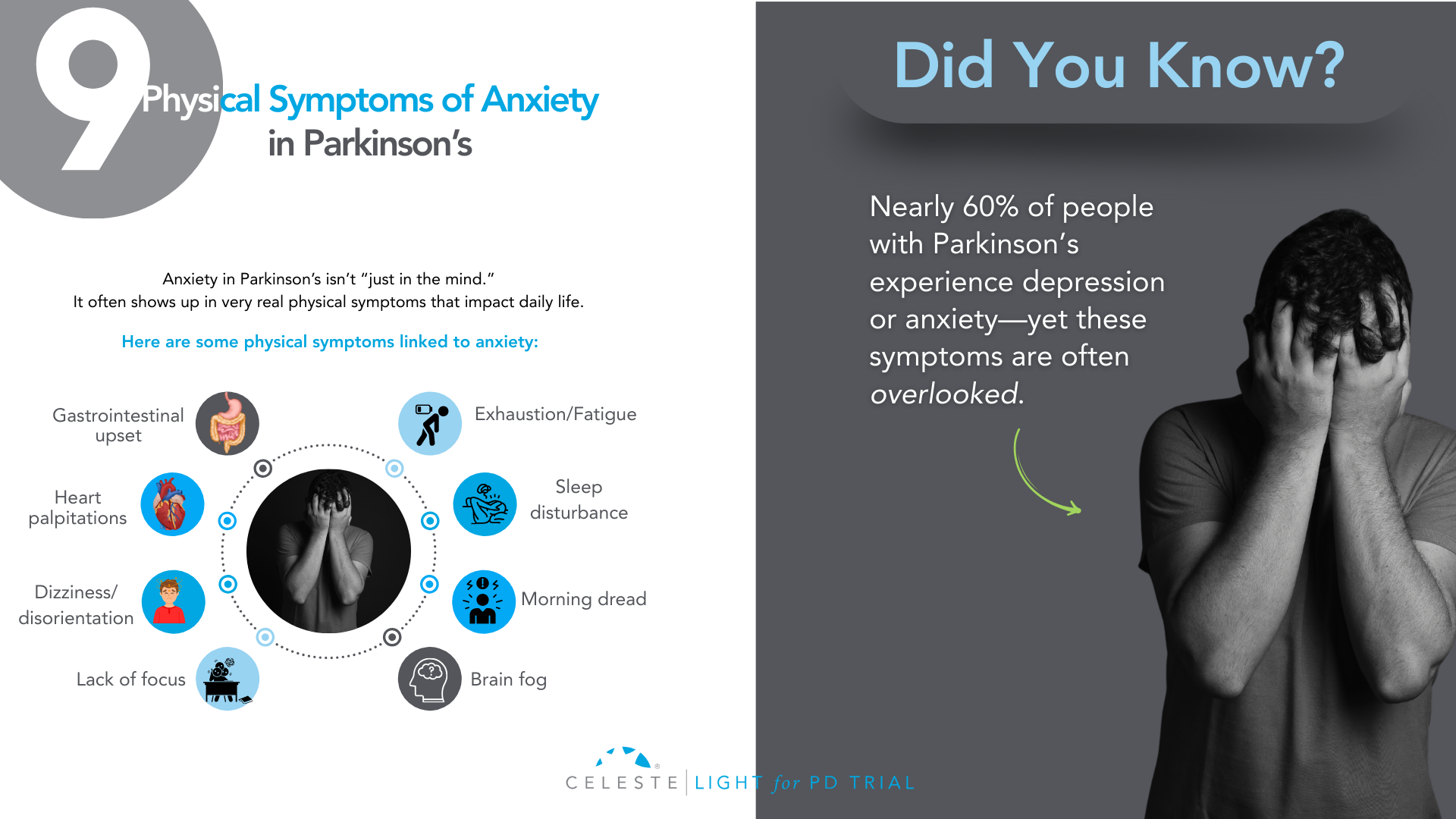

Did you know that at least 50% of people with Parkinson’s Disease (PD) will experience some form of depression during their illness, and up to 40% will face a significant anxiety disorder?

If you’ve been grappling with your mood, you are far from alone. For too long, the conversation around Parkinson’s has focused almost exclusively on the visible, motor symptoms like tremor, stiffness, and slowness.

But as you know, that’s only part of the story. The invisible challenges—the ones that happen inside—are often the heaviest to carry.

Many people, including doctors in the past, assumed that feeling down or anxious was just a natural emotional reaction to being diagnosed with a chronic illness.

While that can certainly be a factor, we now understand something much more profound: depression and anxiety are a core, biological part of the disease itself.

The same changes happening in your brain that affect movement are also affecting the chemistry of your mood.

This isn’t just a side issue; for many, it’s the main issue. It’s the hidden struggle that can impact your quality of life even more than the physical symptoms.

But here is the most important message: it is treatable. You do not have to “just live with it.”

This guide will walk you through this. We will explore why these feelings happen and look at what they look like in PD. This guide will discuss their impact on you and your loved ones. Most importantly, we will cover effective treatments. We will show strategies that can help you. You can reclaim your well-being.

The Celeste (Light for PD) trial shows promising results with a non-invasive approach to managing depression in Parkinson’s. Early findings point toward better support and improved quality of life. Find out how you can get involved.

Why Mood Changes Are Part of Parkinson’s?

To understand why mood changes are so common in Parkinson’s, we need to look beyond dopamine.

While PD is mainly caused by a loss of dopamine-producing cells, this is just one piece of a much bigger puzzle. The neurodegenerative process affects other crucial brain chemical systems as well. Think of it as a “neurotransmitter triad” involving dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine.

Role of Neurotransmitters

- Dopamine: This chemical is famous for its role in movement, but it’s also fundamental to our brain’s reward and motivation system. When the dopamine pathways that govern pleasure and drive are damaged, it can lead directly to apathy (a lack of motivation) and anhedonia (the inability to feel pleasure), which are core symptoms of depression.

- Serotonin: This is perhaps the most well-known mood-regulating chemical. The brain changes in PD also cause a significant loss of serotonin-producing neurons. This isn’t a side effect. It’s a direct hit on the system that helps keep our mood stable, our anxiety in check, and our sleep regulated. This direct link is a major reason why depression is so prevalent in PD.

- Norepinephrine: This chemical is essential for energy, focus, and our response to stress. The part of the brain that produces norepinephrine is also significantly affected in Parkinson’s. A drop in this chemical can contribute to the profound fatigue that so many experience, as well as to both depression and anxiety.

This complex, multi-system chemical imbalance explains so much. It tells us that what you’re feeling is real and has a physical cause. It also highlights one of the most compelling pieces of evidence: depression and anxiety often show up before any motor symptoms appear, sometimes by several years.

This strongly suggests that the mood-regulating parts of the brain are among the first to be affected by the disease process. Recognizing this can be empowering. It reframes your emotional struggles from a personal failing into a manageable symptom of your condition, just like a tremor or stiffness.

What Does Depression and Anxiety Look Like in Parkinson’s?

One of the biggest hurdles to getting help is that depression and anxiety don’t always look the way you’d expect, especially with Parkinson’s in the picture. There’s a significant and confusing overlap between the symptoms of PD and the symptoms of a mood disorder.

This clinical mimicry is a major reason why mood disorders are so often missed. You might feel fatigued and assume it’s “just the Parkinson’s.” Your family might see your reduced facial expression (hypomimia or “masked face”) and think you’re withdrawn or disinterested, when in reality it’s the PD affecting your facial muscles.

This is why it’s so critical to talk specifically about how you’re feeling on the inside, not just what’s showing on the outside.

Let’s break down how these conditions can manifest:

Depression in Parkinson’s can include:

- Major Depressive Disorder: This is what most people think of as clinical depression, involving a persistent low mood, loss of interest or pleasure, and other symptoms that make it hard to function.

- Minor Depression or Dysthymia: This is actually more common in PD. You may not meet the full criteria for major depression, but you experience a chronic, low-grade sadness and other depressive symptoms that still significantly impact your quality of life.

- Intense Feelings of Despair: We need to address this with care and honesty. For some, depression can lead to intense feelings of despair and even thoughts of not wanting to be alive anymore. If you ever find yourself having these thoughts, it is a medical emergency and a sign that the depression has become severe. Please understand that these thoughts are a symptom of the illness, and they can be treated. It is crucial that you reach out for help immediately—contact your doctor, a support hotline, or a trusted person in your life without delay.

The Celeste (Light for PD) trial shows promising results in addressing depression in Parkinson’s. This innovative research is exploring an innovative and non-invasive approach to improve your parkinson’s symptoms. Learn more and see if participation is right for you.

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD): This is a state of constant, excessive worry and nervousness that you can’t control. It can be accompanied by physical symptoms like a racing heart, sweating, or even a worsening of your tremor.

- Panic Attacks: These are sudden, intense episodes of overwhelming fear. In PD, they are often linked to medication “off” periods, when your motor symptoms return as your medication wears off. This can be terrifying, making you feel like you’re having a heart attack or can’t breathe.

- Social Phobia: This is an intense fear of being embarrassed or judged in social situations. It’s often driven by self-consciousness about visible symptoms like tremor, walking difficulties, or dyskinesias. This can lead to avoiding friends and family, causing profound isolation.

How Mood Impacts Your Life and Your Family?

If you’ve ever felt that your mood is a bigger problem than your tremor, you are not alone. Study after study has confirmed that for people with Parkinson’s, depression and anxiety are the single biggest factors that determine a person’s overall quality of life.

It’s not just about feeling sad; these mood states create a vicious cycle of disability that can touch every aspect of your life.

- Worsening Symptoms: Anxiety is known to make tremors worse. Both depression and anxiety are linked to more severe freezing of gait and the difficult “on-off” fluctuations.

- Undermining Self-Care: Depression saps the motivation you need to stick with your medication schedule, do your physical therapy exercises, and stay socially active—all things that are absolutely critical for managing Parkinson’s effectively.

- Accelerating Cognitive Decline: Mood and thinking are deeply connected. Untreated depression can make cognitive issues like problems with focus and attention worse, and over time, may even speed up the rate of cognitive decline.

This ripple effect extends far beyond the individual, placing an enormous strain on the family unit. For caregivers, managing a loved one’s psychiatric symptoms is often more distressing and exhausting than dealing with physical disabilities.

The caregiver’s well-being is directly tied to the patient’s mental state. It’s an incredibly stressful role, and studies show that a huge percentage of caregivers experience burnout and even clinical depression themselves.

Supporting the mental health of the person with Parkinson’s is one of the most important things we can do to support the health of the entire family.

Taking the First Step: Getting the Right Diagnosis

Given the challenge of symptom overlap, you have to be your own best advocate. Don’t wait for your doctor to ask about your mood. In the limited time of a neurology appointment focused on motor symptoms, it can easily be overlooked. You need to start the conversation.

Saying something as simple as, “I’d like to talk about how I’ve been feeling emotionally,” can open the door.

To help identify the problem, your doctor can use simple screening tools. These are short questionnaires that can quickly flag whether you need a more in-depth evaluation.

One of the most recommended for PD is the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15). It’s useful because it focuses more on the psychological feelings of depression and asks fewer questions about physical symptoms that overlap with PD.

The goal of screening isn’t to give a final diagnosis, but to identify that there’s an issue that needs attention. The gold standard is always a full evaluation with a trained mental health professional, like a psychiatrist or neuropsychologist, who can fully understand the nuances of your situation and recommend the best course of action.

Building Your Treatment For Depression and Anxiety in Parkinson’s

Pharmacology is a key part of the treatment plan for many people. It’s about rebalancing the brain chemistry that the disease has disrupted. While no antidepressant is officially FDA-approved specifically for Parkinson’s, several types have been shown to be safe and effective.

Note: This information is for educational purposes only. We do not recommend self-treatment or medication. Please consult a healthcare professional for your Parkinson’s symptoms and receive personalized care options.

Available Options

- SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors): These are drugs like sertraline (Zoloft) or citalopram (Celexa). They are often the first choice because they are generally well-tolerated. They work by increasing the amount of available serotonin in the brain.

- SNRIs (Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors): These are drugs like venlafaxine (Effexor) or duloxetine (Cymbalta). Because we know that both serotonin and norepinephrine are depleted in PD, these dual-action agents can be a very logical and effective choice.

- TCAs (Tricyclic Antidepressants): An older class of drugs, like nortriptyline, has some of the strongest evidence for effectiveness in PD. However, they come with more side effects (like confusion, dry mouth, and constipation) that can be especially problematic for older adults, so they are usually reserved for cases where other medications haven’t worked.

- Dopaminergic Medications: Sometimes, optimizing your Parkinson’s medication can itself have a positive effect on mood. Certain dopamine agonists (like pramipexole) have been shown to have antidepressant effects. And for anxiety or panic linked to “off” periods, adjusting the timing and dosage of your levodopa is often the most important intervention.

The key is working closely with your doctor. Finding the right medication and the right dose can be a process of trial and error, as suggested or followed by a healthcare specialist.

A thoughtful doctor will practice “symptom-focused prescribing,” choosing a medication that not only helps your mood but whose side-effect profile might help another symptom. For example, if you have depression and insomnia, a more sedating antidepressant might be a great choice.

Non-Medication Strategies For Depression and Anxiety in Parkinson’s

Medication is only one part of the solution. A truly comprehensive plan must include non-pharmacological approaches that empower you with skills and strategies to manage your mental health.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): CBT is considered a first-line treatment for depression and anxiety in PD. It’s not just “talk therapy.” It is a practical, skills-based approach that teaches you how to identify, challenge, and change the negative thought patterns and behaviors that keep you stuck. For example, it helps you challenge thoughts like “I’m a burden to my family” and work on behavioral activation—scheduling small, achievable, and enjoyable activities to counteract withdrawal and apathy.

- Physical Exercise: Exercise might be a miracle drug for Parkinson’s. A huge body of evidence shows this. Regular activity is a powerful treatment. It’s effective for depression and anxiety. It boosts brain chemicals. It improves sleep. It gives you a sense of control. Find something you enjoy and do it consistently. This can be walking, Tai Chi, or yoga. It can also be a boxing class for PD.

- Social Connection: Isolation is fuel for depression. A lack of social support is one of the biggest risk factors for developing a mood disorder in PD. This is why support groups—either in person or online—can be a lifeline. Connecting with other people who truly “get it” reduces feelings of isolation and provides a space to share experiences and coping strategies.

You’re Not Alone—The Power of an Integrated Care Team in Parkinson’s Depression and Anxiety

Navigating Parkinson’s can feel like trying to coordinate a dozen different specialists who don’t talk to each other. The future of high-quality PD care is moving away from this fragmented system toward an integrated, multidisciplinary team model.

This means having a team of professionals who work together, with you and your family at the center. Your team might include:

- Your Movement Disorder Specialist, who manages the overall disease.

- A Psychiatrist or Psychologist, for medication management and therapy.

- A Clinical Social Worker, to help you connect with community resources.

- Physical, Occupational, and Speech Therapists, whose work to improve your function and independence has a huge positive impact on mood.

In this model, everyone is on the same page, working toward the same goal: improving your overall well-being.

Conclusion

Your emotional well-being is not a “soft” issue. It is not a secondary concern. It is central to your care. The depression and anxiety you feel are real. They are biological. They are treatable.

The first step is to acknowledge the struggle. Start a conversation with your doctor. Talk to your loved ones. Adopt a proactive and multimodal approach. Combine medications with other strategies.

Use therapy, exercise, and social connection. You can effectively manage your mood. Living with Parkinson’s is a journey. It has many challenges. But you don’t have to let this struggle define you. Bring it into the light. This is a crucial step. It helps you live well with Parkinson’s.

A New Ray of Hope: The LIGHT for PD Clinical Trial

For those looking for innovative, non-medication, non-invasive, and at-home approaches, there is promising research underway.

This study is the LIGHT for PD Trial, which is investigating the use of light therapy as a home-based treatment to potentially manage non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s.

This approach is being explored as a safe, accessible way to potentially improve mood by helping to regulate the body’s internal clock. The trial especially shows promising potential in addressing depression in Parkinson’s.

However, it is close to its end with only 40 last sign-ups left.

So, if you are interested in exploring new treatment options and participating in important research, we encourage you to speak with your doctor or search online for the “LIGHT for PD Clinical Trial” to learn more about the study and see if you might be eligible to participate.

Introduction

If you’re living with Parkinson’s disease (PD), you might have a deeply personal understanding of what fatigue truly means.

It’s a feeling that goes far beyond the simple tiredness you might experience after a long day.

Many describe it in profound terms: an “unrelenting and non-ending tiredness,” a “total absence of energy,” or a sensation so overwhelming it feels “impossible to move.”

This isn’t just being tired; it’s a pervasive, profound exhaustion that sleep doesn’t seem to touch.

If this sounds familiar, please know you are not alone, and what you’re experiencing is very real.

Fatigue is one of the most common and challenging non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s, affecting more than half of all individuals with the condition.

For nearly a third of people with PD, it is their single most disabling symptom—often rated as more burdensome than the more visible motor symptoms like tremors or stiffness.

It can appear early, sometimes even before a diagnosis, and its impact on quality of life is immense, affecting work, hobbies, and the simple joy of connecting with loved ones.

This exhaustion can also bring an emotional weight. Many people with PD feel misunderstood, sometimes labeled as “lazy” or “apathetic” when, in reality, they are battling a legitimate, physiological symptom of their condition.

This article is designed to be your comprehensive guide to understanding Parkinson’s-related fatigue. We’ll explore what it is, where it comes from, and most importantly, provide some strategies to potentially help you manage your energy and reclaim your life.

Understanding Parkinson’s Fatigue: More Than Just Being Tired

To effectively fight back against fatigue, we first need to define our opponent.

Parkinson’s-related fatigue is a complex symptom, and recognizing its unique characteristics is the first step toward managing it.

What is PD-Related Fatigue?

In clinical terms, Parkinson’s fatigue is a profound sense of physical or mental exhaustion that isn’t reliably improved by rest. It’s an unpleasant feeling of lacking the energy to perform routine activities.

This exhaustion can show up in two main ways, either separately or together:

- Physical Fatigue: This is a deep weariness in your body. You might feel “run down,” like you’ve completely run “out of gas,” or as if your limbs are made of lead. This feeling can often intensify during “off” periods when your medication’s effects are wearing off.

- Mental (Cognitive) Fatigue: This is a kind of “brain fog.” It makes it difficult to concentrate, pay attention for extended periods, or even find the mental energy to start a project. It’s a feeling of mental sluggishness that can be just as debilitating as physical exhaustion.

Fatigue vs. Sleepiness vs. Apathy vs. Depression

One of the biggest hurdles in getting the right help for fatigue is that the word “tired” can mean so many different things. Let’s clear up the confusion, because telling these states apart is critical for finding the right solutions.

- Fatigue vs. Sleepiness: This is the most important distinction. Fatigue is a lack of energy, while sleepiness is the need to sleep. Someone with fatigue feels utterly exhausted but may not feel drowsy or able to fall asleep. While sleep problems are common in PD and definitely make fatigue worse, sleepiness is usually relieved by a nap. Fatigue, on the other hand, often lingers even after rest.

- Fatigue vs. Apathy: Apathy is a lack of motivation or interest. A person experiencing apathy might not want to engage in an activity. In contrast, a person with fatigue often desperately wants to do things but feels they simply don’t have the physical or mental fuel in the tank.

- Fatigue vs. Depression: There’s a significant overlap here, as fatigue is a core symptom of depression. However, many people with Parkinson’s experience severe fatigue without being clinically depressed. Treating depression can certainly improve fatigue if they coexist, but it may not eliminate the fatigue that stems directly from the disease itself.

The Pervasive Impact on Daily Life

The ripple effects of fatigue are far-reaching. It’s an unpredictable symptom that can make planning your life feel impossible. Simple tasks can become monumental efforts.

You might start a project, only to find your energy depleted after just 15 minutes. To avoid this crash, you might start avoiding activities you once loved, leading to social isolation and physical deconditioning.

This creates a “fatigue hangover,” where the exertion of one day can leave you drained for several days to follow, stripping the pleasure from life’s most meaningful moments.

The “Why”: The Causes of Fatigue

So, where does this profound exhaustion come from? The answer is complex. Fatigue in Parkinson’s isn’t caused by a single factor but by an intricate web of primary and secondary contributors.

Primary Fatigue:

For many, fatigue is a primary symptom of Parkinson’s, meaning it’s a direct result of the changes happening in the brain. It’s not just a reaction to other symptoms. The neurodegenerative process in PD affects more than just dopamine; it disrupts other neurotransmitter systems, like serotonin, which are closely linked to energy and arousal. This is why fatigue can appear so early in the disease and why its severity doesn’t always match the severity of motor symptoms.

Secondary Contributors:

On top of being a primary symptom, fatigue is often amplified by a host of secondary factors:

- The Sheer Effort of Movement: The motor symptoms of PD are physically draining. Constant tremors, the muscle rigidity that forces you to work against your own body, and the slowness of movement (bradykinesia) all demand an enormous amount of energy for even the simplest tasks.

- Medication Side Effects: Some of the very medications used to manage PD, particularly dopamine agonists, can cause fatigue and daytime sleepiness. Furthermore, fluctuations in levodopa levels can lead to energy crashes as the medication wears off.

- Sleep Disorders: Over 75% of people with PD struggle with sleep. Conditions like insomnia, REM Sleep Behavior Disorder (acting out dreams), Restless Legs Syndrome, and sleep apnea lead to fragmented, poor-quality sleep, which naturally fuels daytime fatigue.

- Mood and Mental Health: The link between fatigue and mood is a two-way street. Depression and anxiety, both common in PD, are powerful drivers of fatigue.

- Other Medical Conditions: It’s crucial to rule out other common causes of tiredness. Treatable conditions like anemia, thyroid issues, or vitamin deficiencies can be significant contributors.

The Vicious Cycle of Fatigue and Deconditioning

Understanding this cycle is perhaps the most empowering concept for managing fatigue. When you feel exhausted, your natural instinct is to rest and avoid activity. While this makes sense in the short term, over time, it leads to weaker muscles and reduced cardiovascular fitness—a state known as deconditioning.

Here’s the trap: when you’re deconditioned, your body has to work much harder to perform any task. This creates a greater sense of effort and exhaustion, which reinforces the belief that activity is the enemy. The less you do, the weaker you become, and the more fatigued you feel. Breaking this cycle is the key to long-term management.

A Multi-Faceted Approach to Managing Fatigue

While there’s no magic bullet for Parkinson’s fatigue, you have the power to make a significant difference. A proactive, multi-pronged approach can help you conserve energy, build stamina, and improve your quality of life.

A. Start with Your Healthcare Team

Your first step is to partner with your neurologist and primary care physician for a thorough investigation. This should include a review of your symptoms to distinguish fatigue from other issues, blood tests to rule out secondary medical causes, and an evaluation for sleep disorders. A comprehensive review of your medications is also critical to ensure they are optimized and not contributing to the problem.

B. Movement as Medicine: Your Guide to Exercising with Fatigue

It sounds completely counterintuitive, but exercise is the single most effective, evidence-backed strategy for combating fatigue in Parkinson’s. Regular physical activity breaks the cycle of deconditioning, improves sleep, boosts mood, and helps your brain use dopamine more efficiently.

- Aerobic Activity: Aim for at least 150 minutes per week of activities like brisk walking, cycling, or swimming.

- Strength Training: Use weights, resistance bands, or your own body weight at least twice a week to rebuild muscle.

- Balance and Flexibility: Practices like Yoga and Tai Chi are fantastic for improving the efficiency of your movements.

- Getting Started: Consult a physical therapist who specializes in PD. Start slow—even 5-10 minutes counts—and gradually build up. Most importantly, find an activity you genuinely enjoy.

C. Work Smarter, Not Harder: The Art of Energy Conservation

Managing fatigue is as much about spending your energy wisely as it is about building it. The “4 Ps” are a great way to remember these strategies:

- Prioritize: Decide what must get done today and let the rest go. Focus your limited energy on what matters most to you.

- Plan: Structure your day to balance activity and rest. Schedule demanding tasks for your “on” times when you feel your best.

- Pace: This is key. Break large tasks into smaller chunks and take frequent rest breaks before you feel tired.

- Position: Sit down whenever possible for tasks like dressing or cooking. Use adaptive equipment to minimize bending and reaching.

D. Fueling for Function: The Role of Diet and Hydration

Good nutrition provides the building blocks for energy. Focus on a balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and lean proteins. Avoid sugar and processed foods that lead to energy crashes. Hydration is non-negotiable—dehydration is a common and sneaky cause of fatigue. Aim for 6-8 glasses of water a day. Also, talk to your doctor about the “protein effect,” as timing your protein intake away from your levodopa doses can improve your medication’s effectiveness.

E. Rest and Recharge: Mastering Sleep and Strategic Napping

Improving your “sleep hygiene” is critical. Stick to a consistent sleep schedule, create a relaxing bedtime routine, and make sure your bedroom is cool, dark, and quiet. If you need to nap, keep it short (10-30 minutes) and take it in the early afternoon to avoid disrupting your nighttime sleep.

How to Talk to Your Doctor About Fatigue

Because fatigue is a subjective symptom, it can be hard to describe its impact to your doctor. The best way to bridge this gap is to come prepared with data. Keep a simple fatigue diary for a week or two before your appointment. Track your energy levels (on a scale of 1-10), your activities, your medication times, and your sleep quality. This transforms a vague complaint into actionable information that helps your doctor identify patterns and potential solutions.

A New Horizon in Managing Parkinson’s Fatigue

Living with Parkinson’s fatigue is an undeniable challenge, but it does not have to define your life. By understanding its roots and implementing a proactive management plan, you can take meaningful steps to reclaim your energy and engage in the activities that bring you joy.

Here at Photopharmics, we are dedicated to exploring new frontiers in managing the symptoms of Parkinson’s. We believe that innovative approaches can complement traditional therapies to address the unmet needs of the PD community.

That’s why we are pioneering the use of specialized light therapy—a non-invasive approach designed to potentially improve both motor and non-motor functions, including the pervasive fatigue that so many experience.

Our clinical trial, Light for PD, is currently underway, and it’s designed with you in mind. It’s a completely at-home trial, meaning no travel is required. Participants can use the therapy in the comfort of their own homes during their usual evening activities, like reading or watching TV.

If you are looking for new ways to manage your Parkinson’s symptoms and contribute to groundbreaking research, we invite you to learn more.

Visit lightforpd.com to see if you or a loved one may be eligible to participate in this pivotal trial. Together, we can work toward a brighter future for everyone living with Parkinson’s disease.