Introduction

The tremor. The stiffness. The deliberate slowness of movement. These are the hallmarks often associated with Parkinson’s disease.

But what if these very same symptoms point to something else entirely?

This is the complex reality of Parkinsonism. It encompasses a range of conditions that mimic Parkinson’s disease, creating diagnostic challenges for even experienced clinicians.

While slowness (bradykinesia), rigidity, and resting tremor are key indicators, they are not exclusive to Parkinson’s disease.

This diagnostic overlap necessitates careful evaluation by a neurologist to distinguish between Parkinson’s disease and other forms of Parkinsonism.

What makes Parkinsonism particularly complex is its ability to mimic Parkinson’s disease, creating challenges in pinpointing the exact cause of symptoms.

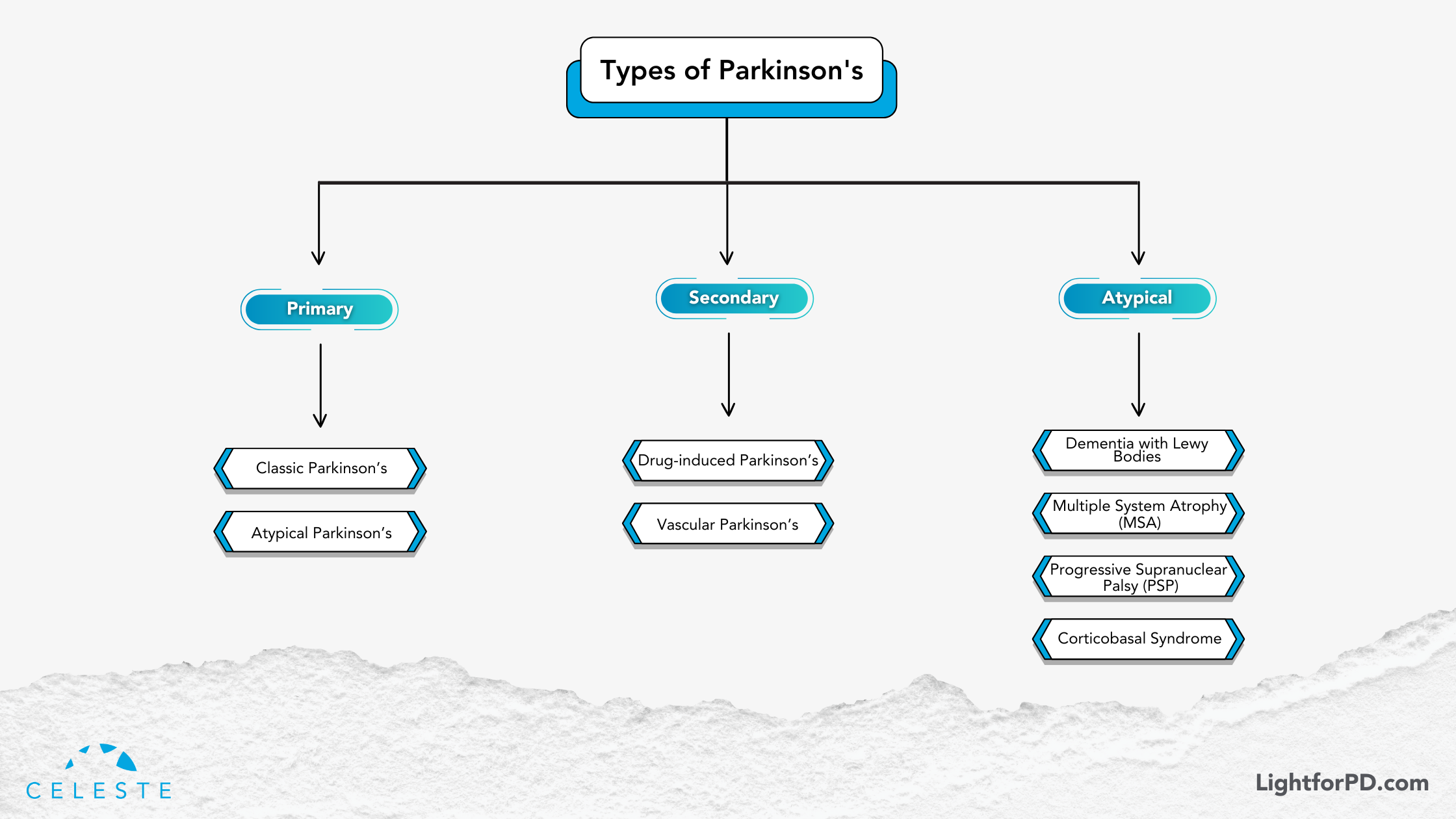

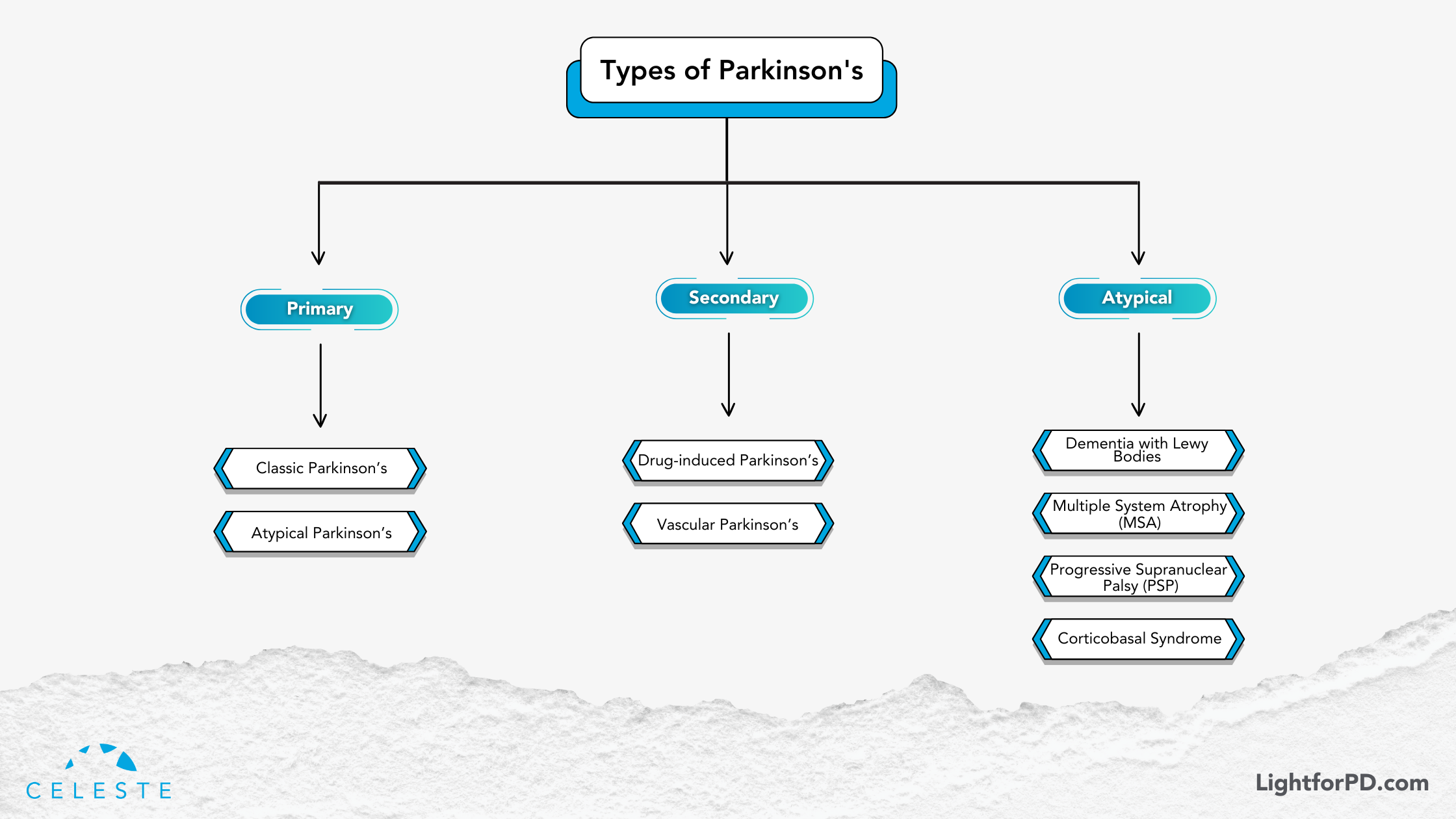

It’s important to understand that Parkinsonism is not a single disease but rather a spectrum of disorders categorized as primary and secondary.

In this blog, we’ll explore the most common conditions associated with Parkinsonian symptoms, shedding light on their differences and helping you navigate this intricate topic with greater clarity.

Whether you’re a patient, caregiver, or simply curious, this guide will give you a deeper understanding of the types of Parkinsonism and their unique characteristics.

Parkinsonism Classification

Parkinsonism is broadly categorized into two main types: primary and secondary. Let’s explore each in detail.

Primary Parkinsonism

Primary Parkinsonism refers to conditions where the underlying cause is a neurodegenerative process—a gradual decline in specific brain cells. This category includes PD itself, as well as a group of related disorders known as atypical Parkinsonian disorders.

Parkinson’s Disease (PD)

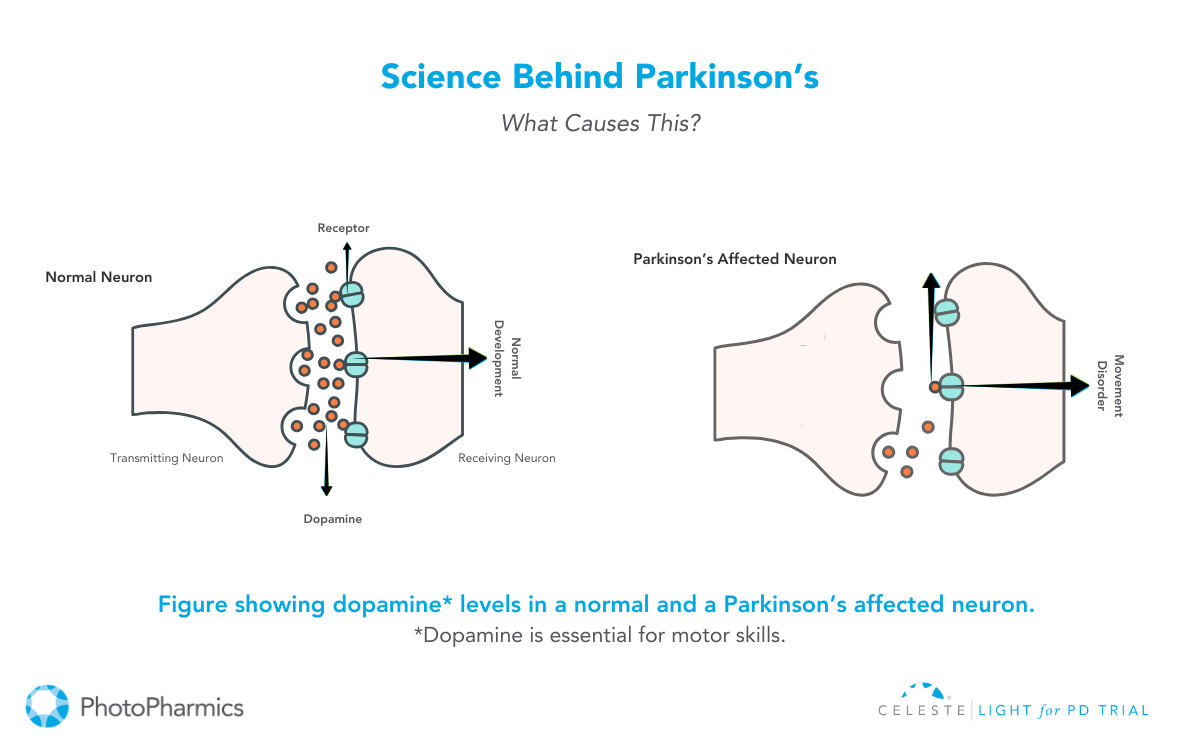

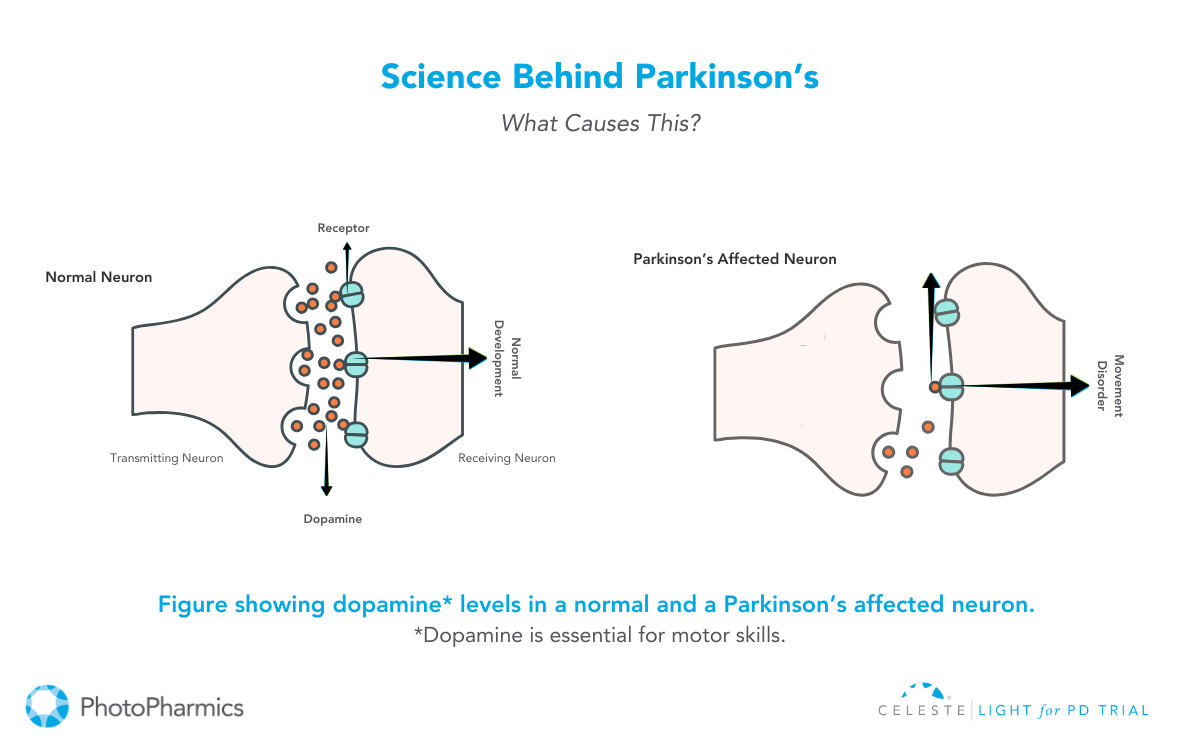

This is the most common form of Parkinsonism. It’s characterized by the progressive loss of dopamine-producing neurons in the brain. This leads to classic motor symptoms: tremors at rest, bradykinesia (slowness of movement), rigidity (stiffness), and postural instability (balance problems). PD typically responds well to levodopa, a medication that converts to dopamine in the brain, replenishing the depleted stores.

Atypical Parkinsonian Disorders

These conditions share some symptoms with PD but have distinct features and often respond differently to treatment. They include:

- Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB): This disorder is characterized by the presence of Lewy bodies (abnormal protein deposits) in the brain, similar to those found in PD but with a different distribution. In addition to motor symptoms, DLB is marked by fluctuating cognition, visual hallucinations, and REM sleep behavior disorder. Levodopa may offer some benefit for motor symptoms, but often less effectively than in PD, and can sometimes worsen psychiatric symptoms.

- Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP): PSP is characterized by early balance problems with frequent falls, difficulty with eye movements (especially looking downwards), rigidity in the neck and upper body, and cognitive changes. Unlike PD, tremor is usually not prominent in PSP. Levodopa typically provides minimal relief.

- Multiple System Atrophy (MSA): MSA is a rapidly progressive disorder affecting multiple systems in the body, including the autonomic nervous system (which controls involuntary functions like blood pressure and digestion), the cerebellum (which coordinates movement), and the basal ganglia (involved in motor control). Symptoms vary depending on the specific systems affected but can include parkinsonism, cerebellar ataxia (problems with balance and coordination), autonomic dysfunction (e.g., dizziness, bladder problems), and speech difficulties. Levodopa is generally not very effective in managing MSA.

- Corticobasal Degeneration (CBD): CBD is a rare disorder characterized by progressive motor and cognitive decline. Motor symptoms can include rigidity, dystonia (sustained muscle contractions), apraxia (difficulty with skilled movements), and alien limb phenomenon (involuntary movements of a limb). Cognitive changes can include problems with language, executive function, and visuospatial skills. Levodopa is usually not helpful in CBD.

Secondary Parkinsonism: When External Factors Play a Role

Secondary Parkinsonism arises from identifiable external factors, such as medications, toxins, or other medical conditions. Unlike primary Parkinsonism, the symptoms may be reversible if the underlying cause is addressed.

- Drug-Induced Parkinsonism: Certain medications, particularly antipsychotics, can block dopamine receptors in the brain, leading to Parkinsonian symptoms. These symptoms usually resolve when the medication is stopped.

- Vascular Parkinsonism: This type of Parkinsonism results from small strokes or other vascular problems in the brain that affect the areas responsible for motor control. Symptoms can be more variable than in PD and may include lower-body parkinsonism (affecting mainly the legs). Levodopa is typically not effective.

Other Secondary Causes: Other potential causes of secondary Parkinsonism include head trauma, infections, and exposure to certain toxins.

The Levodopa Response: A Key Differentiator

A crucial distinction between PD and many other forms of Parkinsonism is the response to levodopa. While PD typically shows a good initial response to this medication, atypical Parkinsonian disorders and secondary Parkinsonism often show little or no improvement. This difference can be a valuable clue for clinicians in making a diagnosis.

The Importance of Accurate Diagnosis

Differentiating between PD and other forms of Parkinsonism is essential because each condition has a different prognosis and requires tailored management strategies. A neurologist, especially one specializing in movement disorders, is best equipped to make an accurate diagnosis through a thorough neurological examination, medical history review, and sometimes brain imaging.

This information is intended for educational purposes and should not be considered medical advice. Always consult with a qualified healthcare professional for any health concerns or before making any decisions related to your health or treatment.

Diagnosing Parkinson’s Disease

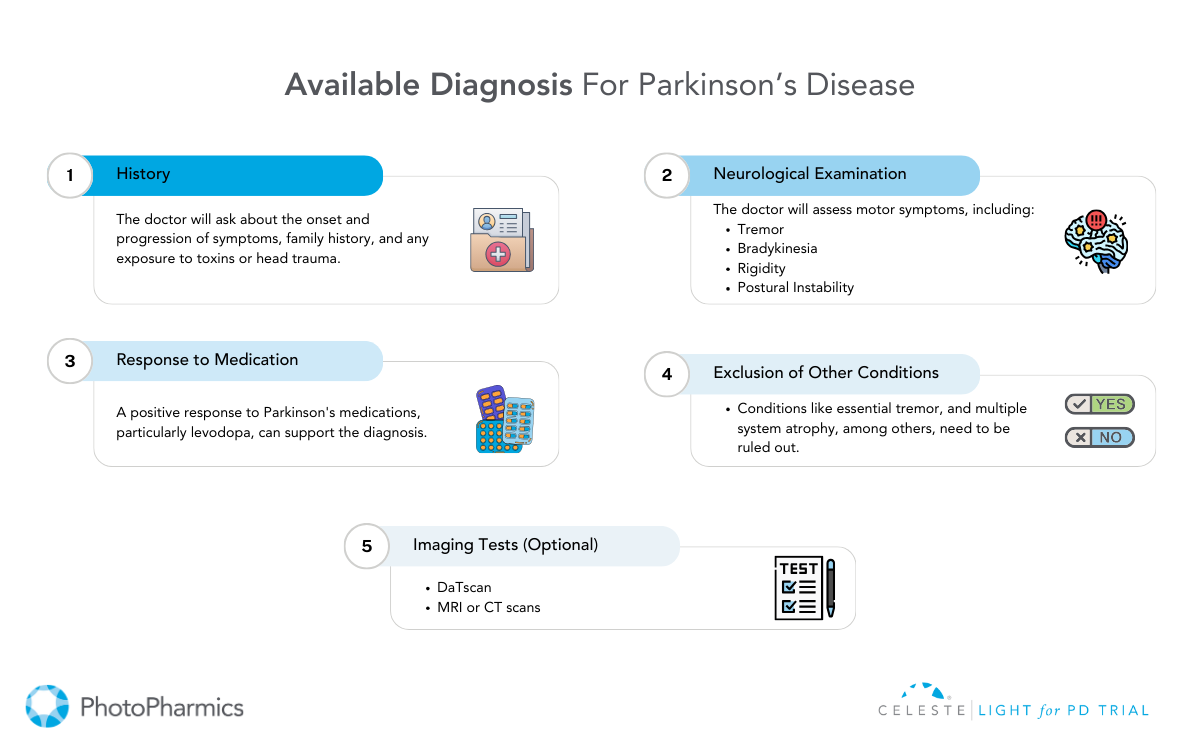

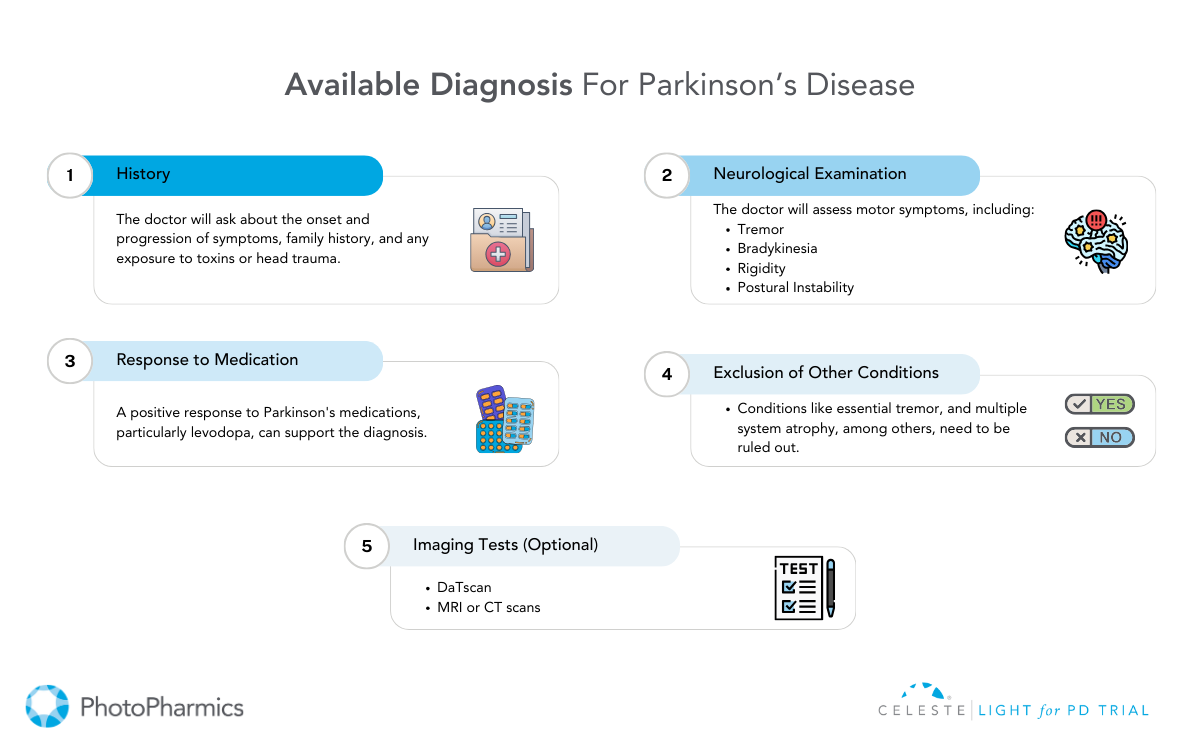

Diagnosing Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a complex process. It’s a clinical puzzle that clinicians piece together using a combination of careful observation, detailed medical history, and neurological examination.

Unlike many other diseases, there is no single definitive test, such as a blood test or brain scan, that confirms a PD diagnosis.

The absence of a “gold standard” biomarker requires diagnosis to focus on motor symptoms while excluding similar conditions.

This clinical diagnostic approach can present challenges, especially in the early disease stages when symptoms are subtle or overlap with other conditions.

This reliance on clinical observation has driven the development and refinement of diagnostic criteria over time.

Evolving Diagnostic Standards

Historically, diagnostic criteria like those from the U.K.’s Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank provided a framework for clinicians.

However, our understanding of PD has evolved significantly, leading to the adoption of newer, more refined criteria from the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society.

These updated standards reflect the latest research and clinical insights, aiming to improve diagnostic accuracy and enable earlier intervention.

The core motor symptoms clinicians look for include: resting tremor (a trembling that occurs when the limb is at rest), bradykinesia (slowness of movement), rigidity (muscle stiffness), and postural instability (balance problems).

These cardinal features, when present in combination and carefully assessed, form the cornerstone of a PD diagnosis.

Beyond the Motor Symptoms: Exploring Prodromal Markers and Advanced Imaging

While motor symptoms are central to diagnosis, researchers are increasingly recognizing the importance of non-motor symptoms. These symptoms are often referred to as prodromal markers, which can precede the onset of motor difficulties by years.

These subtle clues, such as loss of smell (anosmia), REM sleep behavior disorder (acting out dreams), constipation, and mood changes like depression or anxiety, are being investigated as potential early indicators of PD risk.

Additionally, while not diagnostic on their own, advanced imaging techniques like the DaTscan can provide valuable supporting evidence. The DaTscan uses a radioactive tracer to visualize dopamine transporter activity in the brain. It helps to differentiate PD from other conditions with similar motor presentations.

This technology allows clinicians to see if the reduction in dopamine transporter activity is consistent with PD, further strengthening the diagnostic picture.

Ongoing research into biomarkers holds the promise of even earlier and more precise diagnostic tools in the future. This will potentially allow for earlier interventions to slow disease progression.

A Brighter Future: Exploring Light Therapy for Non-Motor Symptoms

Beyond the motor challenges of Parkinson’s, non-motor symptoms such as sleep disturbances, mood disorders, and fatigue can significantly impact quality of life. As research advances in diagnosing Parkinson’s, innovative approaches are also emerging to help manage the condition’s impact.

For instance, Light for PD (our ongoing Parkinson’s clinical trial) is exploring the benefits of light therapy for managing non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s. This non-invasive, at-home therapy offers a promising option to improve the quality of life for those living with PD. By targeting symptoms such as sleep disturbances and mood changes, Light for PD provides a gentle, science-backed way to complement existing treatment plans. If you or someone you know is navigating Parkinson’s, consider joining this trial to explore a new pathway to relief.

For more information to check your eligibility, visit www.lightforpd.com.

What is Parkinson’s?

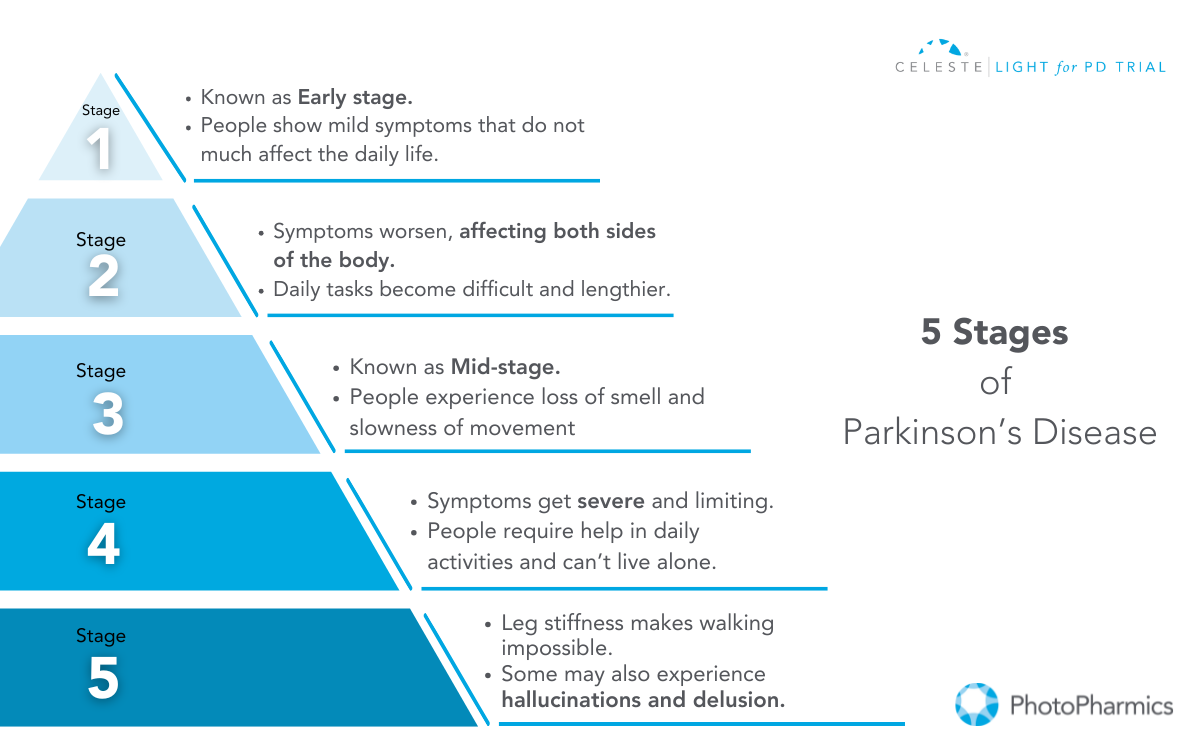

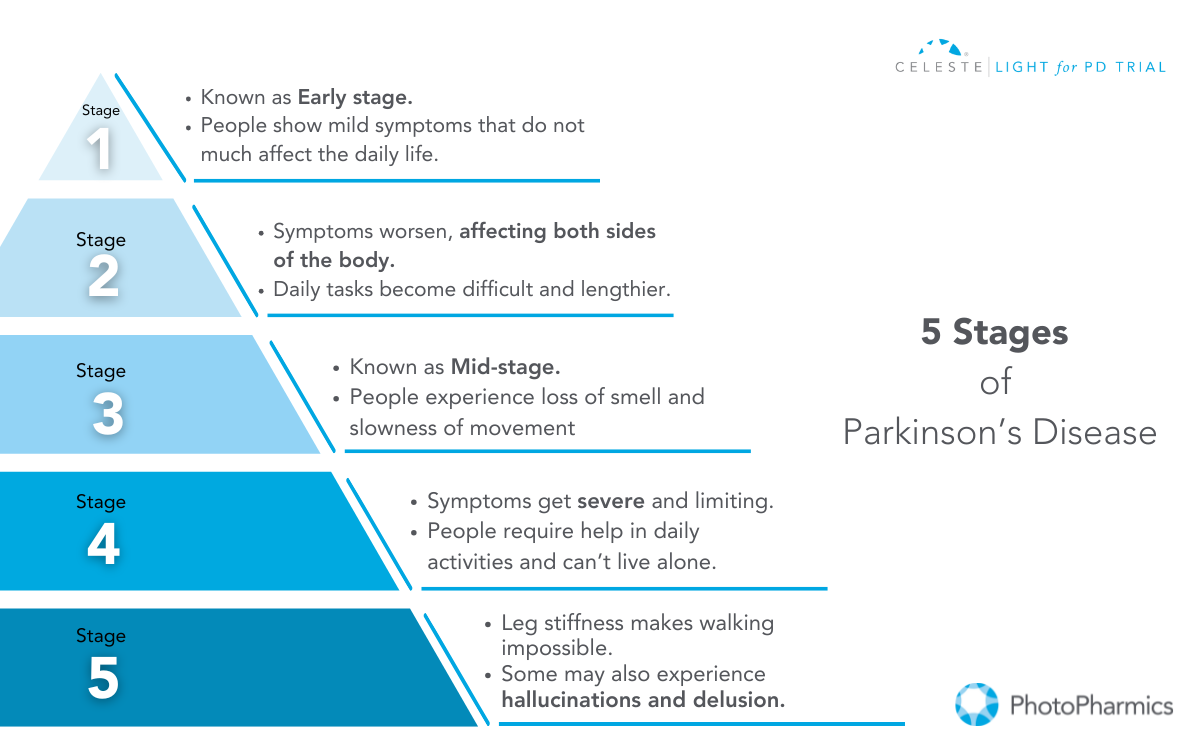

Parkinson’s Disease (PD) is a complex neurodegenerative disorder that affects the nervous system and progressively worsens over time.

While motor symptoms—such as tremors, stiffness, and slow movement—are often the most observable and commonly associated with the condition, Parkinson’s encompasses a broader spectrum of challenges.

Non-motor symptoms (NMS), including anxiety, depression, apathy, and sleep disturbances, can occur early in the disease’s course, sometimes even before motor symptoms appear. Together, these symptoms profoundly impact the daily lives of those with Parkinson’s.

Currently, there is no cure available to treat the disease; however, medicines, therapies, and certain lifestyle changes may help you manage and slow the progression of Parkinson’s symptoms.

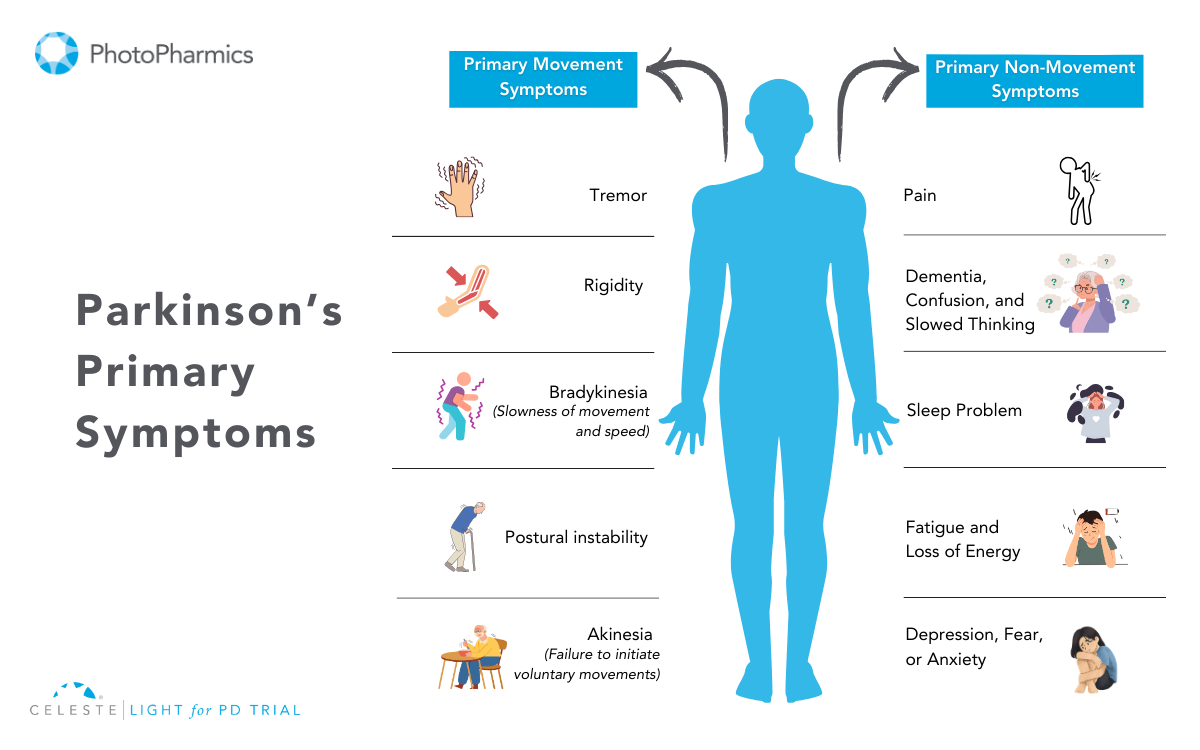

Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease

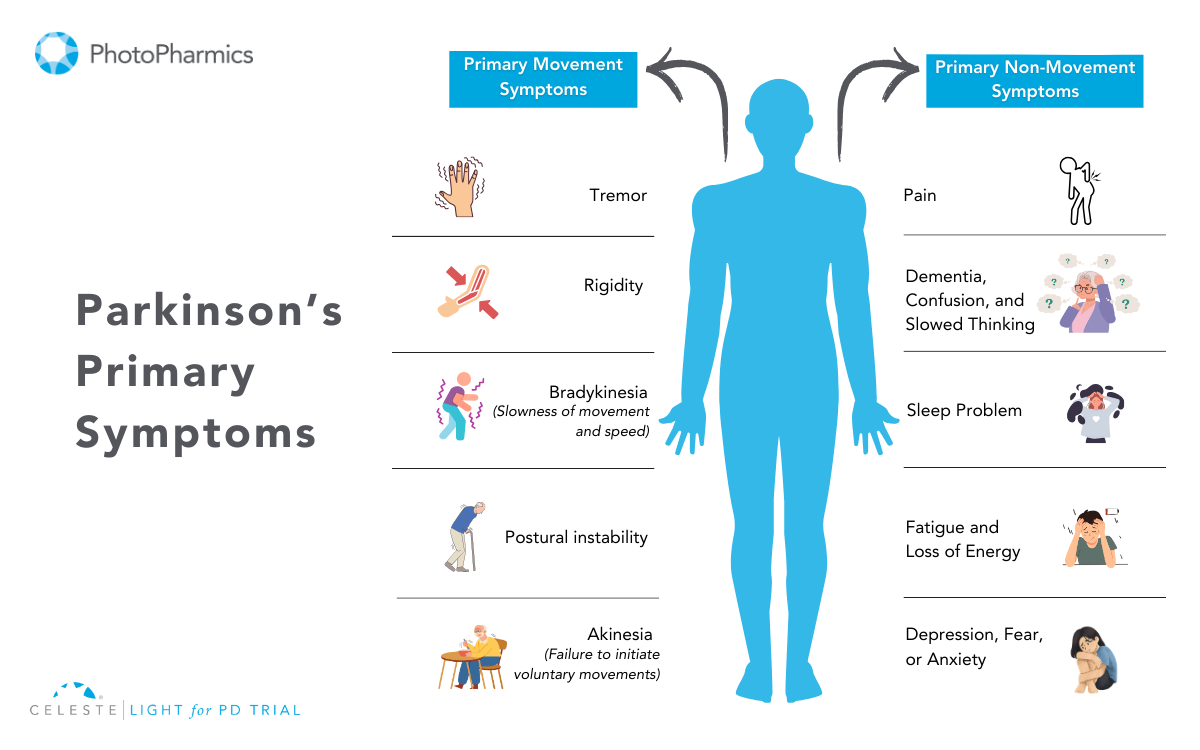

Parkinson’s symptoms are typically categorized into two types: motor (movement) and non-motor (non-movement) symptoms. Both play significant roles in shaping the overall experience of living with PD.

Motor Symptoms

Motor symptoms arise from the brain’s reduced ability to regulate movement due to the loss of dopamine-producing cells. These symptoms can vary in severity but often have a significant impact on daily life.

Here’s an overview of key motor symptoms:

- Tremor: Tremor is one of the hallmark symptoms of PD, typically beginning in the hands or fingers and occasionally affecting the foot or jaw. It is most noticeable when the person is at rest or under stress. A common sign is the “pill-rolling” motion, where the thumb and forefinger rub together rhythmically. Interestingly, the tremor usually subsides during sleep or purposeful movements.

- Slowed Movement: Bradykinesia, or the slowing of spontaneous movement, can make routine tasks like dressing, showering, or eating much harder. Activities that were once quick and effortless may become prolonged and laborious. Additionally, facial expressions might diminish, leading to a “masked face” appearance.

- Balance or Posture Problems: Postural instability and balance issues are common in PD, leading to a stooped posture and a higher risk of falls. Individuals may develop a distinctive “Parkinsonian gait,” characterized by quick, shuffling steps (festination) and reduced arm swing. Freezing of movement, where a person temporarily feels stuck in place, can also occur.

- Small Hand-Writing: Micrographia, or abnormally small handwriting, often becomes evident in individuals with PD. Letters may appear cramped and harder to read, reflecting the motor difficulties associated with fine hand movements.

- Muscle Stiffness or Rigidity: Rigidity affects most people with PD, causing muscles to remain tense and resistant to movement. This can lead to discomfort, aches, and reduced range of motion. When another person attempts to move the arm or leg, it may move in short, jerky motions, often referred to as “cogwheel rigidity.”

Non-Motor Symptoms

Non-motor symptoms often emerge early, sometimes years before motor symptoms, and significantly impact emotional, mental, and physical well-being.

The non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s include:

- Mental Health Issues (Anxiety/Depression): Parkinson’s affects more than just movement; it also deeply influences mental well-being. Many individuals experience anxiety and depression. Anxiety manifests as uncontrollable worry, while depression can lead to sadness, loss of energy, and decreased interest in daily activities. These mood disturbances are not just a response to the diagnosis but a part of the disease itself, rooted in changes within the brain.

- Digestion Problem: Constipation and other digestive issues are common due to the slowing of the digestive tract caused by Parkinson’s. This can make it harder for individuals to maintain proper nutrition and can lead to discomfort if not managed effectively.

- Sleep Problem: Sleep disturbances, such as trouble falling asleep, restless nights, or excessive daytime sleepiness, are prevalent in Parkinson’s. Conditions like REM sleep behavior disorder (acting out dreams) can disrupt rest and pose safety risks. Some sleep issues may be linked to medications or the disease itself.

- Loss of Smell: Loss of smell is one of the earliest signs of Parkinson’s, often occurring years before motor symptoms. This can affect appetite, as the sense of smell is closely tied to taste and enjoyment of food.

- Urinary Issues: Parkinson’s can disrupt autonomic functions, leading to frequent urination, incontinence, or difficulty emptying the bladder. Constipation is also common due to slowed digestive processes. These issues can significantly affect daily life and require tailored management strategies.

- Speech Problem: Changes in speech, such as a soft or monotone voice, are often noted in people with PD. Some may experience difficulty articulating words clearly or find it challenging to speak at an appropriate volume, which can make communication harder.

- Cognitive Issues: Parkinson’s disease can significantly impact emotional well-being and cognitive function. Apathy, or a lack of motivation, is common and may affect daily activities. Cognitive issues range from mild difficulties, like trouble concentrating, to more severe problems, such as dementia. These changes can interfere with social interactions, work, and overall quality of life, making early intervention and management crucial.

- Swallowing or chewing problem: In the later stages of Parkinson’s, swallowing and chewing can become challenging due to weakened muscle control. Food or saliva may accumulate in the throat, increasing the risk of choking or drooling. These difficulties can lead to nutritional deficiencies, necessitating dietary modifications or medical intervention.

Both motor and non-motor symptoms are critical to understanding Parkinson’s as a whole, as they collectively shape the experience of those living with the condition. Recognizing and addressing both types is essential for effective management.

What Causes Parkinson’s?

The exact cause of Parkinson’s remains unknown, but it is believed to result from a combination of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors.

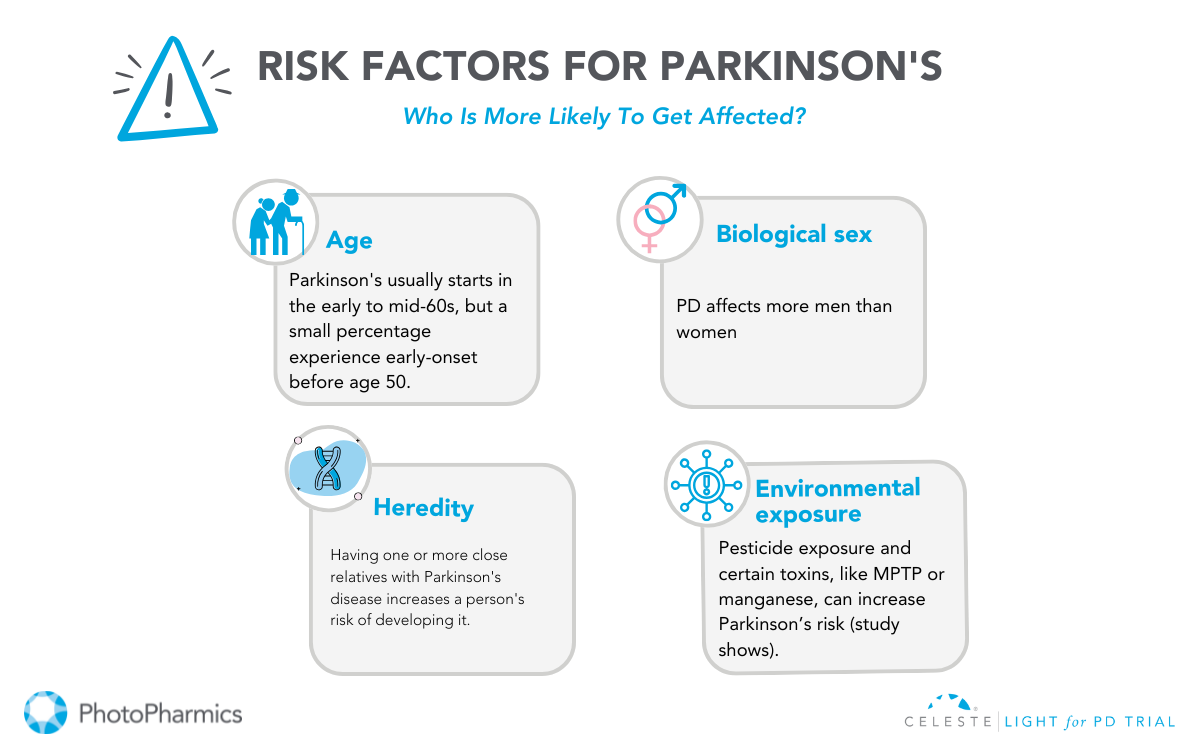

1. Genetic Factors

Genetic mutations contribute to 10-15% of Parkinson’s cases. Specific gene variations, like LRRK2 or SNCA, are linked to a higher risk, but most cases are not directly caused by a single mutation. Genetic research continues to explore these connections for better prevention and treatment strategies.

2. Environmental Exposures

Exposure to pesticides, traumatic head injuries, or certain toxins has been associated with increased PD risk. However, many people with such exposures do not develop Parkinson’s, suggesting other contributing factors are involved.

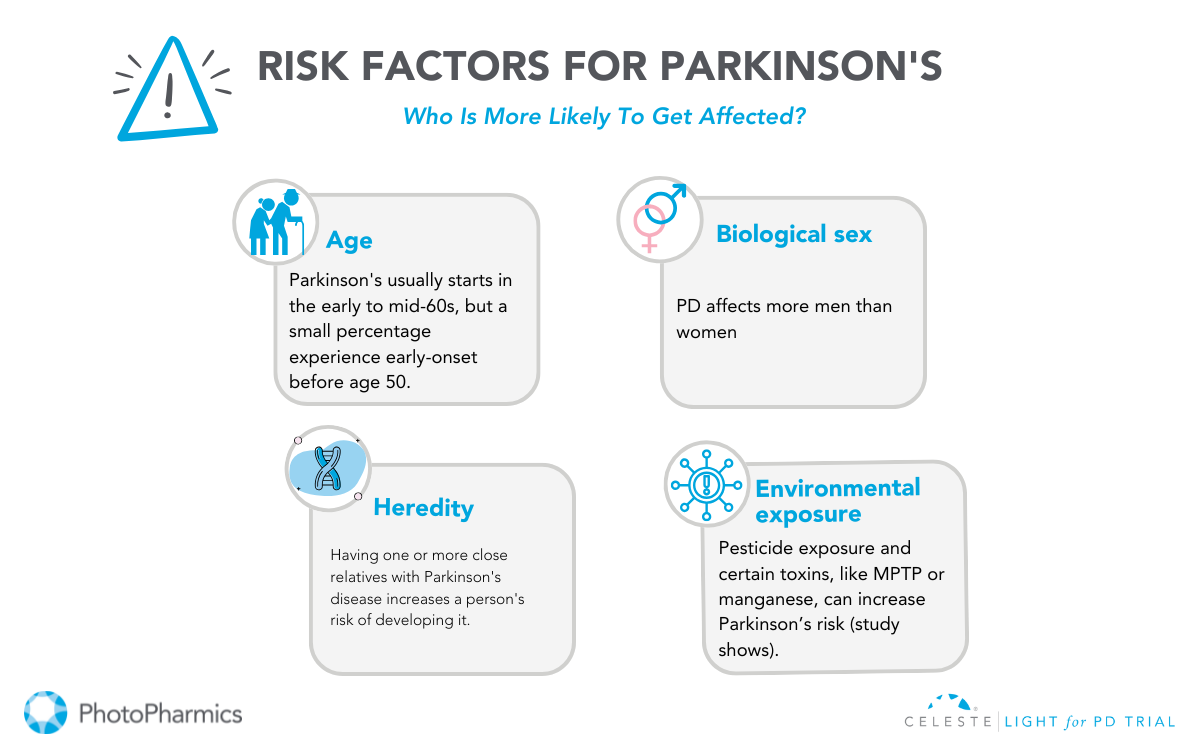

3. Aging

Aging is the most significant risk factor. Most diagnoses occur after age 60, though early-onset Parkinson’s can appear in younger individuals.

4. Brain Changes

The disease involves the loss of dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra, a brain area crucial for movement control. This neuronal loss leads to Parkinson’s symptoms.

PD arises from a complex interplay of factors, and ongoing research is vital to understanding its causes and progression.

Who Can Get Parkinson’s?

Parkinson’s disease, a progressive neurological disorder, predominantly affects older adults. While the exact cause remains elusive, certain factors can elevate the risk of developing this condition.

Age and gender play significant roles, with the risk increasing with age and men being more susceptible. Environmental factors, such as long-term exposure to pesticides and heavy metals, can also contribute to the risk.

Additionally, genetic factors, particularly a family history of Parkinson’s and specific gene mutations, can increase susceptibility.

Other risk factors include REM sleep behavior disorder and traumatic brain injury. It’s crucial to note that while these factors can influence the risk, not everyone with these factors will develop Parkinson’s.

Diagnosis and Treatment of Parkinson’s

While there’s no cure for Parkinson’s, understanding the diagnostic process and treatment options is crucial for managing the condition effectively.

Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease

Diagnosing Parkinson’s Disease (PD) involves a comprehensive evaluation by a neurologist. There’s no single definitive test, but a combination of methods helps identify the characteristic symptoms.

The neurologist reviews the patient’s medical history, conducts a neurological examination to assess motor skills and cognitive function, and may order specialized tests.

Brain imaging techniques like MRI and DaTscan can provide valuable insights into brain structure and function. A careful evaluation of how symptoms respond to medications like levodopa can also aid in diagnosis.

Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease

While there’s no cure for Parkinson’s Disease, various treatment options can help manage symptoms and improve quality of life.

Medication plays a crucial role, with dopamine replacement therapy being the cornerstone. Medications like levodopa increase dopamine levels in the brain, while other drugs mimic its effects or slow its breakdown.

In addition to medication, surgical interventions like deep brain stimulation (DBS) and focused ultrasound (FUS) may be considered for specific cases.

Non-pharmacological therapies, including physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy, complement medical treatments by addressing mobility, daily living activities, and communication challenges.

The journey with Parkinson’s may be challenging, but with a strong support system and the right healthcare provider, you can navigate it more effectively.

Surround yourself with loved ones who can provide emotional and practical support, and explore the wealth of resources available to help make living with Parkinson’s easier and more manageable.

Join the Light in the Fight Against Parkinson’s

Living with Parkinson’s Disease (PD) can be challenging. While medications and surgeries offer some relief, many individuals still face significant non-motor symptoms.

PhotoPharmics is pioneering a non-invasive approach to address these challenges. Our Light for PD clinical trial is seeking participants to evaluate the effectiveness of the Celeste therapeutic light device.

This six-month, at-home study is designed for people aged 45 and older with a Parkinson’s diagnosis and offers up to $500 for full participation.

By joining this clinical trial, you could help revolutionize care while exploring a therapy that might enhance your own well-being.

Check your eligibility today—let’s brighten the future together!